history of trade

Trade in War’s Darkest Hour:

Churchill and Roosevelt’s daring 1941 Atlantic Meeting that linked global economic cooperation to lasting peace and security

I. INTRODUCTION

To read coverage of trade negotiations in the 21st century you’d be forgiven for thinking that trade deals are motivated solely by economic self-interest. Yet a single page of text from 1941 is a powerful reminder that the desire for peace and security drove the creation of today’s global economic system. The global rules that underpin our multilateral economic system were a direct reaction to the Second World War and desire for it to never repeat.

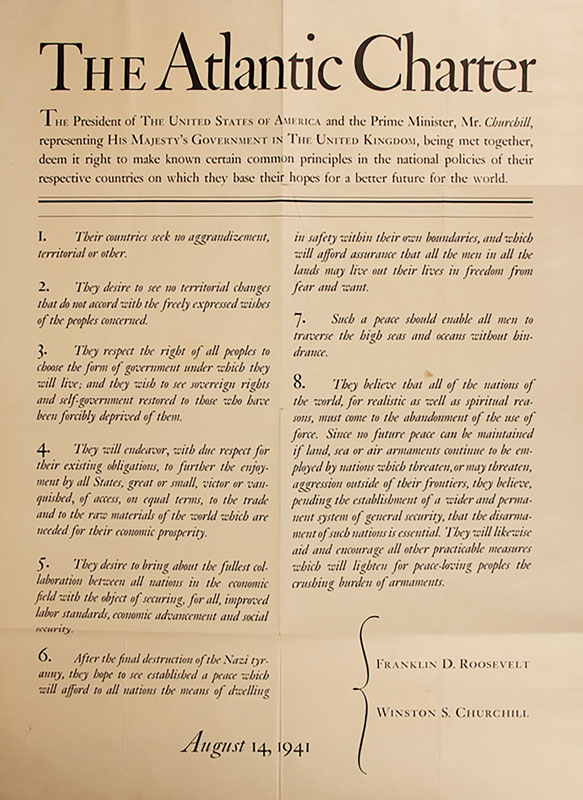

The Atlantic Charter was agreed upon by Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt at a critical moment when the United States was considering entering the war. Comprising 8 succinct clauses, the Charter sets out “common principles” on which both countries based their “hopes for a better future for the world”.

The leaders’ secret meeting, in a desolate bay off Newfoundland, Canada, was considered “the most dramatic personal encounter of the War” and the resulting Atlantic Charter “one of the most remarkable documents in history”.(1)

Few today recall that on 4 August 1941, Winston Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff, in conditions of the greatest secrecy, embarked on a daring mission across the Atlantic Ocean in the battleship HMS Prince of Wales to meet President Roosevelt. The voyage across the Atlantic battleground, at the height of the war, avoiding German U-boats, “was not a pleasure cruise: it was a dangerous occasion”. Everyone in the ship knew that Hitler had never been offered a finer target.(2) The war was at its height, with Germany’s invasion of Russia occurring just six weeks earlier.

As might be expected, Clauses 1, 6 and 8 of the Atlantic Charter refer to the war-time goals of an “established peace” from “Nazi tyranny” and the “abandonment of the use of force”.

However, it may surprise some that Clauses 4 and 5 are economic. They refer to the importance of bringing about “the fullest collaboration between all nations in the economic field” and “to further the enjoyment by all States, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms to the trade … of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.”

Thus, at a time when the world was in the throes of its bloodiest conflict, these two war-time leaders recognised the relationship between global economic collaboration and enduring peace and security. One is necessary for the other. The Charter was not only the genesis of several remarkable achievements of multilateral international economic rule-making, including the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and Bretton Woods institutions, but also paved the way for an unprecedented era of relative peace and security.

Fast forward to today. The value of global economic rules is being questioned by many. This has been coupled with an increase in protectionist trade barriers.

In these troubling times we have a collective responsibility to better communicate the underlying peace and security origins and benefits of global economic rules and architecture to our societies. After 70 years of relative peace, those benefits could easily be forgotten in debates about global trade and economic collaboration. Yet they are one of the greatest legacies of a remarkable but fragile system of multilateral economic architecture.

Churchill and Roosevelt aboard HMS Prince of Wales during the 1941 Atlantic Meeting

II. THE ATLANTIC CHARTER OF 1941

I thought you would like me to tell you something of the voyage I made across the ocean to meet our great friend, the President of the United States. Exactly where we met is secret, but I don’t think I shall be indiscrete if I go as far as to say that it was ‘somewhere in the Atlantic’.

Winston Churchill, by Public Radio Broadcast, 24 August 1941

Churchill and Roosevelt’s secret 1941 Atlantic Meeting off Newfoundland, Canada, was daring and historic. The journalist H. V. Morton accompanied Churchill and published a vivid account of the voyage in 1943. Churchill’s battleship arrived at Placentia Bay off the shores of Newfoundland after five precarious days crossing the Atlantic battleground avoiding German U-boats. They were greeted by the impressive sight of several American warships. President Roosevelt on the heavy cruiser USS Augusta had also journeyed in secret. The entire American press was speculating on his location, with few believing the official line that the President was “enjoying his cruise” on a fishing holiday up the New England coast in his yacht, the Potomac.

The Atlantic Charter is a one-page document of 8 succinct clauses that set out “common principles” on which those countries “base their hopes for a better future for the world”.

Clauses 1, 6 and 8 refer to immediate war-time goals: “no [territorial] aggrandizement”, to see “established a peace” from “Nazi tyranny”, and the “abandonment of the use of force”.

However, Clauses 4 and 5 are notable for their focus on global economic collaboration and access by all States to the trade of the world. They read in full:

Clause 4.They will endeavour, with due respect for their existing obligations, to further the enjoyment by all States, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.

Clause 5.They desire to bring about the fullest collaboration between all nations in the economic field with the object of securing, for all, improved labour standards, economic advancement and social security.

Thus, Churchill and Roosevelt recognised the relationship between international economic collaboration and enduring peace and security. Another leading advocate of the linkage between economic collaboration, access by all States to the trade of the world, and peace and security was then United States Secretary of State, Cordell Hull. He recognised that the Great Depression in the 1930s set off a vicious spiral of trade retaliation that saw two-thirds of world trade wiped out, worsened unemployment, and eventually contributed to the outbreak of devastating war. Hull was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1945 for “co-initiating the United Nations”. He remains best known, however, for his conviction of international trade as a pathway to peace. Already in 1937, he had declared that: “I have never faltered, and I will never falter, in my belief that enduring peace and the welfare of nations are indissolubly connected with … the maximum practicable degree of freedom in international trade”.(3)

The Atlantic Charter was the springboard for remarkable achievements of multilateral international economic rule-making, including the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade of 1947 and the Bretton Woods institutions (of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund). Peace and prosperity through trade and economic collaboration was the basic objective of these initiatives. Those aspirations were largely realised, leading to an unprecedented era of relative peace and security - certainly compared with the chaos and destruction of the first half of the twentieth century.

Thus, the global rules that underpin the multilateral economic system were created as a direct reaction to World War II and a desire for enduring peace and security.

III. WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE ATLANTIC CHARTER TO INFORM GLOBAL GOVERNANCE

It seems that the Atlantic Charter is instructive in three aspects: (i) vision, (ii) courage, and (iii) pragmatism.

A. A vision – based on lessons from history

The Atlantic Charter was always intended to be a bold document that looked to the future. “I have an idea that something really big may be happening – something really big”, said Churchill to the journalist Morton, when leaving his ship to meet Roosevelt.(4)

It is striking how much of the document looks beyond the immediate, and very real, wartime threat. The sole and explicitly stated purpose of the Charter was for the President and Prime Minister “to make known certain common principles … on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world”. It is unapologetically visionary.

Churchill was not shy in describing the significance he attached to the meeting and Atlantic Charter. “This meeting was bound to be important” he said, six days after his return. “It symbolises in a form and manner anyone can understand in every land and every clime, the deep underlying unities” for a better world. “We had the idea when we met there, the President and I, that without attempting to draw final and formal peace aims or war aims, it was necessary to give all peoples … a simple, rough and ready wartime statement of the goal towards which the British Commonwealth and the United States mean to make their way”. The intent was to provide “guidance of the fortunes of the broad and toiling masses in all continents, and our loyal effort, without any clog of self-interest, to lead them forward”. Roosevelt similarly saw this as a forward-looking document, beyond the war effort alone, “to guide our policies going down the same road”.(5)

Critically, their vision for a better future for the world was based on lessons from history. Both leaders did not want to repeat errors of the past – where the relationship between international economic collaboration and peace and security had been ignored with disastrous consequences.

Churchill was explicit in his radio broadcast that the Atlantic Charter contains “distinct and marked differences” from the attitude adopted by the Allies after the First World War, “and no one should overlook them”. In particular, “instead of trying to ruin German trade by all kinds of additional trade barriers and hindrances, as was the mood in 1917, we have definitely adopted the view that it is not in interests of the world” that any “nation should be unprosperous or shut out from the means of making a decent living for itself and its people by industry and enterprise.” This perspective was widely held within the United Kingdom, as demonstrated by documents of the War Cabinet from that time.(6)

This view aligned with that in the United States. Secretary of State Cordell Hull had held this vision for a long time as did Harry Dexter White who was to become a key architect of the Bretton Woods system. For White, economic collaboration through the post-war institutions – that in time would lead to the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and World Trade Organisation – was critical to avoiding new wars. Writing in 1942, White articulated this view as follows: “Just as the failure to develop an effective League of Nations has made possible two devastating wars within one generation, so the absence of a high degree of economic collaboration among the leading nations will, during the coming decade, inevitably result in economic warfare that will be a prelude and instigator to military warfare on an even vaster scale”.(7)

Both countries had seen how the politicisation of trade and exchange controls had been ruthlessly used by Nazi Germany as a tool of economic aggression to subjugate neighbouring Balkan states in the prelude to World War II.

Furthermore, neither country wanted to repeat the disastrous global escalation of ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ retaliatory trade barriers of the 1920s and 1930s. These included the United States’ Smoot-Hawley tariffs in 1929 which, according to the League of Nations, triggered an “outburst of tariff-making activity in other countries, partly at least by way of reprisals.”(8) The United Kingdom responded with emergency tariffs in 1931 and the 1932 Ottawa Agreement to deepen discriminatory imperial preferences with its dominions (principally Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa). Similar protectionist and discriminatory trade policies were adopted by many other countries. The outcome was a dramatic 66 percent decline in world trade by 1933, which aggravated the Great Depression and contributed to the Second World War.(9)

There can be no doubt that in 1941, both the United States and the United Kingdom recognised the relationship between global economic collaboration, open trade, and enduring peace and security.

B. Courage – beyond immediate self-interest

The Atlantic Charter also required courage. This was obviously represented by the very real dangers involved in Churchill’s Atlantic crossing at the height of the war. Morton’s account of the voyage captures those perils. Reading it 75 years on, I’m struck by Morton catching his breath on the first night in Placentia Bay “in amazement, for the ships were not blacked out!” Morton had seen nothing like that due to two years of wartime curfews in Britain. He describes how HMS Prince of Wales, which had entered the bay that morning in full camouflage, “was un-darkened for the first time in her life.”(10) The HMS Prince of Wales, one of the British Navy’s key battleships, was sunk under enemy fire less than four months later.

Another less-obvious courage, however, was demonstrated in leaders making politically-difficult concessions beyond immediate economic self-interest to reach an agreement of long-term benefit. This political courage was not evident to me when I commenced this paper but seems a historical lesson in leadership that should not be overlooked.

As noted above, the key driver behind Clauses 4 and 5 on economic collaboration was to avoid a repeat of the conditions that led to the Second World War.

However, Clause 4 was also intended to address the United States’ deep concerns with the United Kingdom’s system of imperial preferences that had deepened under the 1932 Ottawa Agreements. These preferential tariffs discriminated against foreign countries in favour of Commonwealth trade. They were granted at the expense of United States food and manufacture exporters, whose share of British imports had fallen considerably by 1936. Hull lamented that Britain had “closed like an oyster shell” under the Ottawa system.(11) Dismantling these British preferences was a key political priority for the United States.

The Second World War strengthened the United States’ hand in achieving this goal. Congress had agreed to support Britain through the Lend-Lease Act of March 1941 via the transfer of billions of dollars of equipment and supplies. In exchange, there was an unspecified commitment that Britain provide a “direct or indirect benefit which the President deems satisfactory”. This became known as “the consideration” and had a profound impact on the post-war economic system, allowing the United States considerable influence. Hull aimed to use “the consideration” to extract a pledge to abolish imperial preferences and secure Britain’s support for a non-discriminatory international trade regime.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the United Kingdom had a strong domestic lobby desperate to maintain imperial preferences. The United Kingdom’s chief economic negotiator was none other than renowned economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynes was a strong proponent of imperial preferences, driven by a conviction that government economic planning, including controls on trade, would be required to ensure full employment in the post-war period for the beleaguered British economy. Keynes was no diplomat and dismissed suggestions of non-discriminatory trade between the two countries as the “lunatic proposals of Mr Hull”.(12)

A further complication was the precarious political situation of the Churchill government. Churchill was leader of a coalition wartime government in which a significant faction strongly supported close ties to the colonies. They “threatened revolt, possibly bringing down the government, if a promise was made to dismantle imperial preferences.”(13)

These competing domestic political interests played out in the negotiation of Clause 4 of the Atlantic Charter. Churchill’s first draft proposed to merely “strive to bring about a fair and equitable distribution of essential produce … between the nations of the world”. Roosevelt responded with the counterproposal for trade “without discrimination”, directly targeting the imperial preferences.

Clause 4 was heavily negotiated over the 3-day Atlantic Meeting. The journalist Morton observed the almost continuous conferences, between the President and Prime Minister and the Chiefs of Staff making up the Council of Placentia: “Launches were in perpetual motion between the Prince of Wales and the President’s cruiser; secretaries and others ran up gangways, disappeared and returned with papers and documents”.(14) Telegrams were constantly being sent back to London and Washington.

Churchill was a free trade supporter but had to deal with the political situation domestically. Any changes to imperial preferences also required consultation with the Dominions. Indeed, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Peter Fraser, who was in London at the time, was woken in the middle of the night to join an emergency meeting of the War Cabinet to consider the text. On the trade clause, Fraser’s view was vital because of the sensitivity of the Commonwealth Dominions. Fraser accepted Churchill’s ultimate compromise as “the importance of having a joint declaration far out-weighs any possible subsequent difficulties”.(15)

Churchill’s compromise text softened Roosevelt’s language by removing reference to “without discrimination” but retained the goal of “access on equal terms” to the trade and raw materials of the world. It is little known that Churchill’s caveats, designed to at least postpone abandoning imperial preferences, created an allergic reaction in the United States’ State Department. Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles reported that the modifications “would destroy completely any value in that portion of the proposed declaration”. For Welles, “if the British and United States governments could not agree to do everything within their power to further, after the termination of the present war, a restoration of free and liberal trade policies, they might as well throw in the sponge and realise that one of the greatest factors in creating the present tragic situation in the world was going to be permitted to continue unchecked in the post-war world”.(16)

Nonetheless, over these strong objections, Roosevelt looked beyond the United States immediate trade interests and position of negotiating power and accepted Churchill’s language. Ultimately, the United States economic interest to dismantle imperial preferences was superseded by long-term foreign policy and security objectives.

This was not the only time that a United States President sacrificed immediate trade interest in favour of foreign policy and security objectives when setting up today’s global trade rules.

This dynamic played out again at the end of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade negotiations in Geneva in October 1947. The United States kept pushing for dismantling the imperial preferences until the final hours of those negotiations, with the United Kingdom holding its line. Ultimately, frustrated United States trade negotiators wanted to exclude the United Kingdom from the GATT. But President Truman recoiled from a walkout, on the advice of the Secretary of State George Marshall of a need to look beyond immediate trade-interest in light of strategic security concerns. A “thin agreement” that would preserve trade cooperation, instrumental to wider United States foreign and security policy, was seen as “better than none”.(17) It is not widely known that United States national security officials, not trade experts, made the ultimate decision regarding the GATT negotiations. Nor is the frustration of the American trade delegation at the end of the inaugural GATT round, that had compromised on “America’s top trade priority – to abolish the discriminatory Ottawa system of tariff preferences”. Yet, as historian Zeiler summarised, “rather than being selfish or unrealistic, U.S. trade policy turned out to be wise.”(18) The GATT paved the way to an unprecedented era of peace and security and, over time, the discriminatory imperial preferences were eliminated.

C. Pragmatism – substance over form

There is no “Atlantic Charter” in the sense of a formal signed document. It was merely approved by the President and Prime Minister while their ships were at anchor on 12 August, allowing for joint announcement of its eight principles. It is astonishing today to think that a document of such influence, agreed upon by the President of the United States and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, after 3 days of intense negotiation over its wording, was never signed and has no formal international legal status.

It is unclear why the Charter was never signed – and there may have been good reason – but with the benefit of 75 years hindsight the Charter offers a lesson that substance can override form in international rule-making. It illustrates that international law “is only one of the elements that go to the making of foreign policy in a hard cold world”.(19) Perhaps its non-binding nature allowed for politically courageous leadership that looked beyond short-term self-interest.

The brevity of the Charter is also striking, certainly compared with most outcomes of international negotiation today. It is perhaps that combination of vision, courage and brevity that allowed the Charter to have such influence, as the genesis of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the Bretton Woods system and the United Nations. It has refreshing clarity of vision unhindered by arcane and technical terms.

The comment from the journalist Morton, writing in 1943, showed significant foresight: “The Atlantic Charter is clearly one of the most remarkable documents in history, and a world that has been taught by bitter experience to view documents and signatures with a certain amount of cynicism may feel that the fact that the Atlantic Charter was not signed, sealed and delivered in the usual manner may argue well for the future of Mankind.”(20)

IV. CONCLUSION

The relationship between global economic collaboration and enduring peace and security is seldom articulated nowadays. Yet long-term peace and security was the undeniable driving force behind the creation of the post-war multilateral economic rules and architecture. Economic cooperation as a platform for peace and security has been replicated with success elsewhere, from the European Union(21) to the Association of South East Asian Nations.(22)

Today, the value of global economic rules is being questioned. This has been coupled with an increase in protectionist trade barriers.

Despite significant discourse on globalisation, we almost never talk of global economic rules and architecture in terms of their peace and security benefits. Yet if we are to erode or dismantle those rules and architecture what are the risks to peace and security?

The purpose of this paper is to describe the underlying peace and security origins and benefits of international economic rules and architecture to our societies. After over half a century of relative peace, those benefits easily could be forgotten in today’s debates about globalisation. Yet they are one of the greatest legacies of a remarkable but fragile system of global economic architecture.

- H.V. Morton, Atlantic Meeting: An account of Mr Churchill’s voyage in HMS Prince of Wales, in August, 1941, and the Conference with President Roosevelt which resulted in the Atlantic Charter, 1943 (Morton) at 11.

- Morton at 10.

- Irwin, Mavroidis, Sykes, The Genesis of the GATT, 2009 (Irwin, Mavroidis, Sykes) at 10.

- Morton at 128.

- G. Hensley, Beyond the Battlefield: New Zealand and its Allies 1939-45, 2009 (Hensley) at 142.

- Perhaps none as influential as the War Cabinet economist James Meade who had published a short book in 1940 titled The Economic Basis of a Durable Peace. Meade was awarded the Nobel prize in economics in 1977 for his Theory of International Economic Policy.

- B. Steil, The Battle of Bretton Woods, 2013 at 127.

- 1933 League of Nations report, Genesis at 8.

- Irwin, Mavroidis, Sykes at 3-8.

- Morton at 197.

- T. Zeiler “GATT Fifty Years Ago: US Trade Policy and Imperial Tariff Preferences”, 1997, Department of History, University of Colorado (Zeiler) at 710.

- Irwin, Mavroidis, Sykes at 14.

- Irwin, Mavroidis, Sykes at 19.

- Morton at 122.

- Cable to Wellington 1941 in Hensley at 144. Hensley reports that New Zealand Prime Minister Fraser played a further role in the drafting of the Charter, urging an additional statement to Clause 4, in all likelihood the one on “improved labour standards, economic advancement and social security”.

- Foreign Relations of the United States 1941, Irwin, Mavroidis, Sykes at 16, fn 10.

- Foreign Relations of the United States 1947, Zeiler at 714.

- Zeiler at 709.

- Chris Beeby, New Zealand’s International Legal Advisor and subsequent WTO Appellate Body Member, Informal Talk on Legal Work and Negotiation, 1986 (on file with the author).

- Morton at 17.

- The European Union had its origins in economic cooperation but was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize 2012 (for transforming “Europe from a continent of war to a continent of peace”).

- Speech by HE Maris Sangiampongsa, Ambassador of Thailand, celebrating ASEAN at 50 in 2017 (a motivation behind ASEAN was to “change a battlefield into a market place”).