DEPUTY DIRECTOR-GENERAL ALAN WM. WOLFF

More

My thanks to the American Association of Exporters and Importers for inviting the WTO to participate with the World Customs Organization (WCO) in your 99th Annual Conference. The AAEI is very important to the WTO. The WTO exists solely to serve world trade, in which your members are heavily engaged. The topic you have chosen for us to address today is a very relevant one: What is the Future of Trade? Multilateral or Bilateral.

The multilateral trading system — the rules incorporated into the WTO — along with the contributions of the WCO, on the one hand, and regional and bilateral trade agreements, on the other, share the task of regulating global trade. They are complementary. It is not a choice of one or the other, multilateral or bilateral. Each has its strengths and drawbacks.

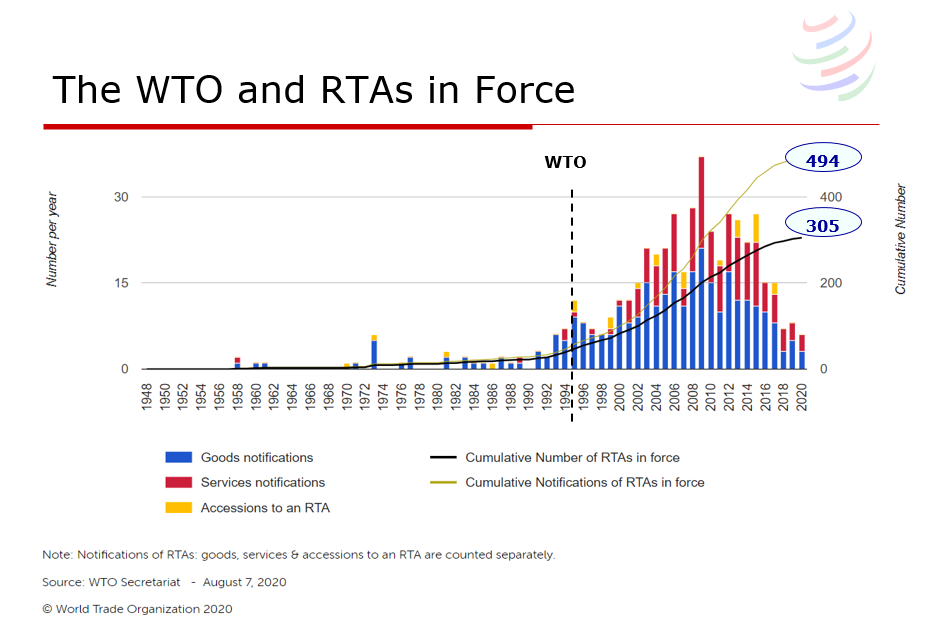

There are currently 305 regional trade agreements (RTAs), that is, sub-multilateral trade agreements, in force which are notified to the WTO, covering goods, services or goods and services. (The number of notifications – 494 - is higher because an RTA having goods and services aspects requires two notifications in accordance to WTO rules; also, there are accessions to agreements and these have to be notified).

Slide {2} shows graphically the data on when RTAs in force were notified to the WTO and cumulatively how many now are in force.

A recent meeting agenda of the WTO’s Committee on Regional Trade Agreements can give you a flavor for the variety of parties involved in RTAs. Reviewed were the Free Trade Agreement between Japan and Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN); the Free Trade Agreement between Hong Kong, China and the Republic of Georgia; the Free Trade Agreement between Peru and Honduras; and the Free Trade Agreement between the GUAM and participating States — the Republic of Moldova, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Ukraine.

The motivations for entering into FTAs vary. In the case of the United States, there are, according to the U.S. Trade Representative’s website, twenty FTAs in force. There was no single unifying set of criteria for concluding these agreements. The USMCA(1) is a regional agreement with neighbors, who have common borders and engage in a very large amount of cross-border trade. Some U.S. FTAs were entered into primarily for geopolitical reasons, underwriting the Middle East peace process, for example. Some prior FTAs, I have been told, came into being for no more profound a reason than to give two heads of state something to announce at a bilateral meeting at their level. The latest U.S. agreements under negotiation are with Japan and Kenya.

In addition to the USMCA, there are other relatively recent regional agreements that are noteworthy:

- The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is a free trade agreement among 11 countries in the Asia-Pacific region: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. The United States actively negotiated for TPP and withdrew from it before ratification. At present, the CPTPP is in force for seven out of the 11 Parties.

- The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) now has 30 member countries that have deposited their instruments of ratification with the African Union Commission. Those AU members are Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, Niger, Chad, Congo Republic, Djibouti, Guinea, Eswatini, Mali, Mauritania, Namibia, South Africa, Uganda, Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire), Senegal, Togo, Egypt, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Sierra Leone, Saharawi Republic, Zimbabwe, Burkina Faso, São Tomé and Príncipe, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Mauritius. Cameroon and Angola. A total of 55 countries are expected to join. Preferential trade under the agreement is expected to start as of 1 January 2021.

- The EU — Mercosur Agreement, not yet in force, covers the 27 members of the European Community (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Republic of Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden), together with Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. This will be one of 75 trade agreements that the EU has negotiated or is negotiating, of which 55 are in force and have been notified to the WTO . The vast majority of these are free trade agreements, and including a few customs unions, for example with Turkey.

Major prospective agreements include:

- The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) — a proposed free trade agreement between the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN — Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, and five of ASEAN's FTA partners — Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. India was originally also a party to the negotiations but has since left — though the door remains open for it to rejoin.

- The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the United States and the European Union (not currently under active negotiation).

What do the RTAs that are in force have in common?

- They are all preferential — they do not extend their benefits to non-signatories. Were there an agreement between Switzerland and Vanuatu, and it provided that the island nation would grant imports of swiss chard entry with no tariffs, and imports of competing products would still pay a 50% tariff, chances are that this would give a major benefit to swiss chard exporters.

- The RTAs all have rules of origin that require enough content from the parties to qualify for zero tariff or other preferential treatment in the participants’ markets.

- They are to cover substantially all of the trade of the signatories, per the WTO rules. However, the WTO rules allow for lesser coverage of RTAs concluded among developing countries only.

- All rest upon the foundation of the rules of the multilateral trading system, the WTO rules. They do not seek to re-negotiate all of the rights and obligations that the signatories have under the WTO agreements. Primarily they add to them.

- The parties’ WTO rights and obligations remain largely intact.

Are RTAs good for world trade?

Why was there an exception made for preferential agreements when the cornerstone principle of the multilateral trading system is exactly the opposite namely, nondiscrimination (most-favored-nation treatment)? The economic theory behind these departures from non-discrimination is that they will result in more trade creation than trade diversion. In concrete terms, non-signatories, we can infer, tolerated the creation of the European common market, the EU-EFTA free trade agreement and EU expansion, not solely for geopolitical purposes, and the North American Free Trade Agreement (revised as USMCA), not just because RTAs in general are authorized by the GATT rules, but based on the belief that there would be net commercial benefits for all nations trading with them.

Chances are good that the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), covering a continent in which intra-continental trade has always been limited, will also meet this qualitative test. The WTO has indicated that it will willingly do all it can, on request, to be of assistance to making the African Continental agreement a success.

Does the future belong to bilateral and regional agreements, and not multilateral agreements?

The simple answer is “no”. The more nuanced answer is that the future belongs to trade agreements of varying geometries. Globalization drives an even greater need for both kinds of agreements, multilateral, such as for e commerce in a digital world, and bilateral/regional/plurilateral agreements wherever important progress can be made on a sub-multilateral level.

With the proliferation of bilateral and regional trade agreements, and the track record of not adding truly comprehensive multilateral agreements to the WTO canon, one could ask whether the WTO, borrowing a phrase from the great Spanish novelist Carlos Ruiz Zafón, is “a relic of a vanished civilization”(2). This is not the case at all.

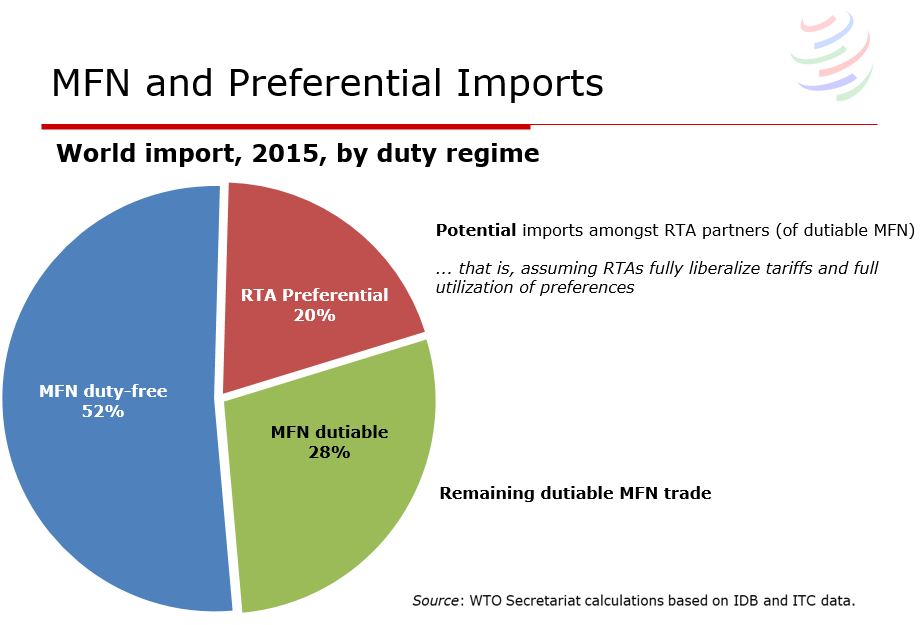

The rules of the WTO cover almost all — 98% — of world trade. These multilateral rules govern the trade relations of its 164 Members, and increasingly of the 23 countries in the process of acceding to the WTO. WTO economists estimate that — despite all the preferential agreements that are in existence — about 80% of world trade is actually conducted on a nondiscriminatory basis. Part of the reason is that a substantial quantity of goods cross borders duty-free. Slide {3} on MFN and Preferential Imports shows this graphically.

More than half of imports in 2015 — 52% — took place at duty-free MFN (non-discriminatory) rates. An additional 28% of imports were dutiable on an MFN basis. Imports under RTA preferential rates only amounted to at most 20% of 2015 imports. This 20% figure is certainly an over-estimate. It is based on assumptions that (1) all trade between Parties is liberalized , (2) that all products are traded under the preferential regime and (3) that all products qualify as originating within the RTA participating countries. Clearly this is not the case.

Another reason for underutilization of RTAs is that if the MFN (the non-discriminatory) rate for a product is low, keeping track of origin is just not worth the effort to quality under an RTA. In the case of electronic components, meeting rules of origin might not be practicable at all. Producers often are not going make special lines of products for many different markets nor are their customers often going to require them to do so just to meet origin requirements.

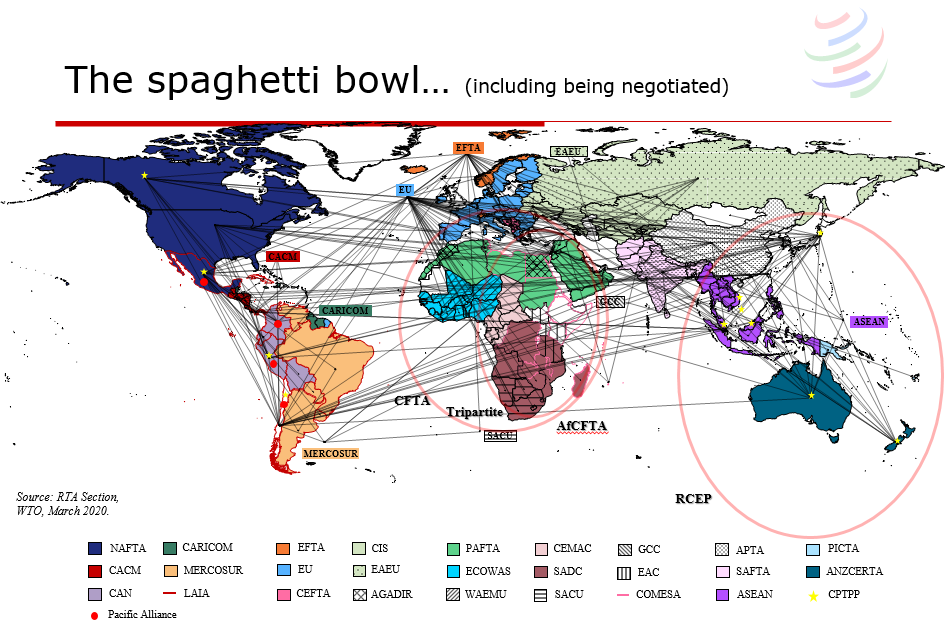

Slide {4} shows a map of both existing RTAs as well as some RTAs that are still under negotiations (for example RCEP). It gives a striking picture of the complex relationships the world of bilateral and plurilateral trade agreements is creating. The map shows that there are multiple overlapping preferential relationships. That means agreements that provide different sets of preferences, rules, perhaps industrial and agricultural standards (TBT and SPS) disciplines, and possibly dispute settlement provisions. And for each RTA, a set of preferential rules of origin with its particular certificate of origin and verification procedures needs to exist. Of course, there can be positive elements beyond preferential tariffs. Some RTAs have provisions for Mutual Recognition Agreements and self-certification by Authorized Economic Operators, which are beneficial for businesses operating in the countries subject to the agreement. One thing is clear. There is a substantial burden on global traders to be aware of, understand if they are to make use of the various benefits these RTAs promise.

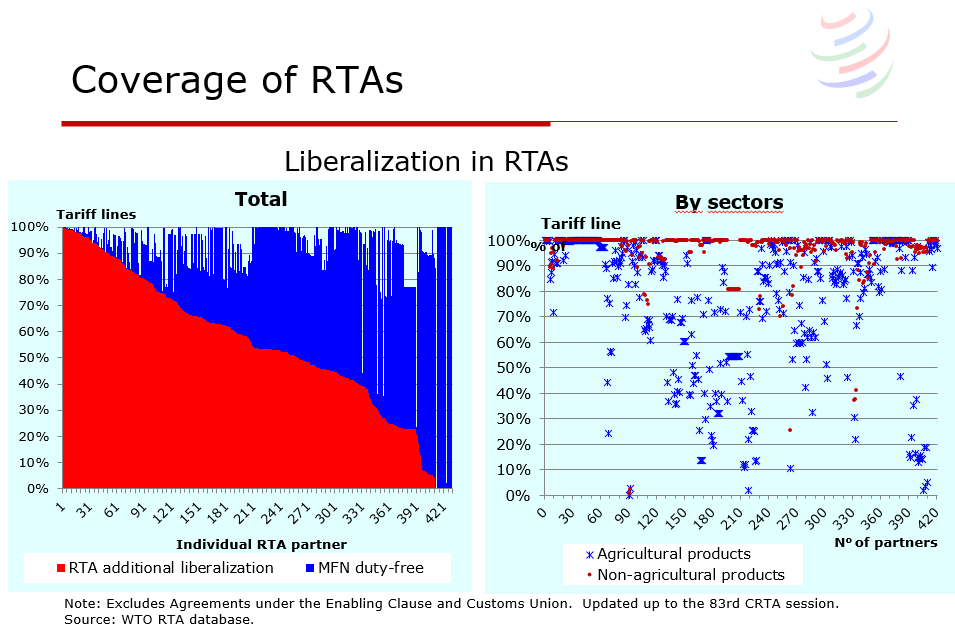

Slide {5} below shows another feature of RTAs. It looks at 200 bilateral relationships under RTAs that have been notified to the WTO. Each point and each bar represents a bilateral relationship under an RTA. In the first chart, in red, you can see the additional liberalization brought by the RTA — once fully implemented. In many instances, this additional liberalization is quite modest. More striking is the second chart. Many RTAs provide limited coverage for agricultural products. The chart plots in blue the percent of tariff lines liberalized in the agricultural sector, and in red that of industrial products. It clearly shows that coverage of the agricultural sector is limited.

All trade agreements, including RTAs, need to respect political realities if the agreements are to be approved and implemented.

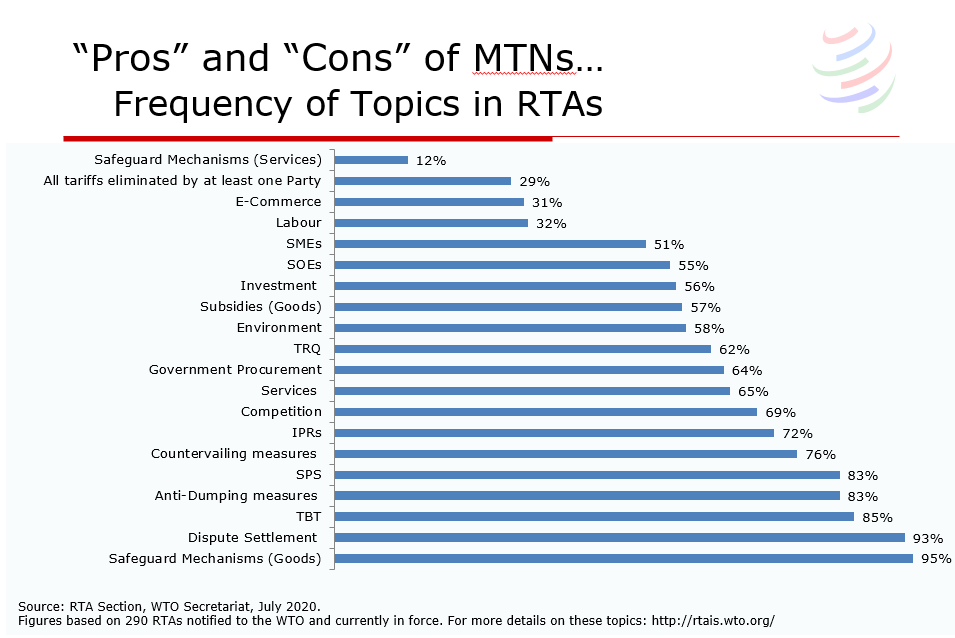

Not all RTAs are alike in their coverage. Slide {6} below shows this graphically. The slide depicts the frequency of certain topics contained in RTAs that have been notified to the WTO. There are a number of lessons one can draw from it. The following few illustrate points what I have already mentioned:

- In terms of liberalization, less than a third of the RTAs foresee at least one of the Parties liberalizing all of its tariffs. In general, sensitive products remain protected, even in RTAs.

- In many instances, where a topic is not dealt with under the WTO, it is also not much regulated in RTAs: for example,

- safeguard disciplines for services, not presently regulated by the WTO, are only present in 12% of RTAs; and

- labor and e-commerce are regulated in less than one-third of the RTAs;

- Services, a major sector of economy for many countries, is only addressed in 65% of the RTAs. In WTO there is a General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS).

In many of the areas addressed by the RTAs, their provisions simply reaffirm or restate the WTO disciplines.

When is an RTA good for world commerce?

From a policy perspective (as opposed to the legal requirements of the WTO), the first criterion for making a judgment of whether an RTA is good for world commerce would be whether it creates more trade than it diverts. That is not a judgment that can be made when an RTA enters into force. Later experience may help answer the question.

The clearest case of an RTA being potentially clearly positive is a regional agreement — in Africa, North America, Europe, or Asia — integrating contiguous countries. Long distance bilateral RTAs, which like all these agreements by definition provide discriminatory preferential access, are each worth examining on their individual merits.

The bottom line of each company engaged in trade, and therefore collectively, determines patterns that international trade will follow. It is very unlikely that many companies participating in international trade would choose to plan their future to consist solely of trade with countries with which its government has negotiated a regional or bilateral trade agreement. That would be too confining, too cramped a view for management of most companies as to their future. COVID 19 has taught us that trade is diverse, it relies on many sources and many markets. A ventilator is made of up to 600 parts sourced everywhere. The demand for medical equipment and supplies is truly global.

There is another metric for judging the value of a regional trade agreement. An RTA can contain substantive provisions that go beyond the present WTO and may create a template for future multilateral negotiations. RTAs can, as in e-commerce, contain paths to solutions to problems not yet solved at the multilateral level. They can serve as experimental platforms to carry the WTO into new fields answering a felt need for the global trading system to be modernized to reflect current trade realities. Ultimately, some of these RTA commitments are incorporated in multilateral agreements at the WTO — such as intellectual property protection.

One reason that sub-multilateral agreements have become so common is not perhaps that they are necessarily superior to broader agreements, but that they are in many cases easier to conclude. Getting agreement among 164 countries, each part of a consensus process, is very challenging, and that is an understatement. This is the primary reason that a variety of joint initiatives among like-minded countries were launched in December 2017 at the most recent WTO Ministerial Conference held in Buenos Aires.

It is claimed that negotiating on a multilateral level is time-consuming. It is. The last major round of trade negotiations, the Uruguay Round, took from 1986 to 1993 and only became effective on January 1, 1995, with the creation of the WTO. The major negotiation prior to that was launched in 1973 following years of preparation and concluded in 1979. Exploratory work for the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement was given a green light in 1996, and negotiations were launched in 2004 after attempts to start in 1999 and 2001 did not succeed. The TFA was concluded in 2013 and went into effect in 2017. It covers most trading countries. The savings to those who are engaged in trade due to streamlining procedures could b ein the range of 2%–15% of the value of the goods traded, according to estimates by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In many cases this saving can be greater than the applicable tariffs. The process of creating the TFA was slow and it is to be implemented only over time, but the TFA is very important for world trade. It was worth the wait.

Lengthy trade negotiations are not specific to the WTO. RTAs are not always concluded with lightning speed.

- Negotiations among the 12 Parties to the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) were based on a four-party agreement signed in 2005. In 2008, the process of negotiating an expansion of the agreement began. It eventually included another eight countries. With the withdrawal of the United States, the revised CPTTP (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership) only entered into force in late December 2018 for at the moment 7 out of the 11 signatories.

- The negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement between the European Union and MERCOSUR took more than 20 years to finalize. The Agreement was substantially finalized in June 2019 but as of today it has yet to be signed and ratified.

What is the future of trade? Multilateral or Bilateral?

Transportation and communications have caused the world to shrink. There is no going back to a smaller global economy having a less interconnected world.

Ways forward will be found to serve international commerce. In some instances, for agreements to be quickly arrived at, they will of necessity have a very limited number of signatories. Singapore and New Zealand when they agreed within weeks of the onset of the pandemic to facilitate trade in COVID-19 related products.

Other agreements will be plurilateral, with a larger number of WTO Members participating. For example, a group of like-minded Members decided in December 2017 that the digital economy needed to have agreed trade rules. This was one of several open plurilaterals launched at that time.

Some agreements that are negotiated plurilaterally provide results on a multilateral basis in accordance with the WTO’s MFN principle. That is the case for the Information Technology Agreement (ITA) — concluded at the Singapore Ministerial Conference in 1996 and expanded in 2015 at the Nairobi Ministerial Conference.(3)

Some subjects do not lend themselves to non-multilateral agreements. They are not susceptible to bilateral or regional-only solutions. They need to be as comprehensive as possible. A few parties are unlikely to agree to more stringent disciplines on agricultural or industrial subsidies. They will want a critical mass of countries to do so. Finding a solution to obtaining disciplines on fishery subsidies requires all interested parties to participate. It is a very difficult subject, but it is making progress and the end may be in sight. It would not be possible for each country with a fishing fleet to agree to limit its own fisheries subsidies when others that have major fishing fleets are not similarly constrained.

Are there hurdles to reaching multilateral agreements? Of course there are. Inclusiveness, reaching consensus is time-consuming. Compromises can dilute a result if the level of aspiration among the negotiating parties is insufficient. On the other hand, dividing the world among those with privileged market access and those without through discriminatory arrangements can only result in a sub-optimal outcome. The WTO, the multilateral trading system, is built upon the principle of non-discrimination. It is inconceivable that there could be a stable and peaceful world built on the principle of discrimination.

Is multilateralism difficult? Of course it is. It is painstaking and slow, and requires strong, sustained leadership, and a willingness of all to create a global public good that will be beneficial to all.

The sole criterion for setting the path for the future of trade agreements, multilateral, regional or bilateral, must be whether those of us who are engaged in this effort are serving you who are engaged in trade.

The current pandemic only underlines the need to find cooperative solutions on a global basis. The twin crises of both world health and the world economy highlight the need for coordination of trade policy and trade policy instruments among all of the WTO’s Members. In a complex world, based on integrated production, global value chains, and ever-increasing digitalization, the only place where all Members can discuss and agree on a set of abiding rules, jointly with a mechanism for settling disputes — is the WTO.

Additional questions

Our host and moderator, AAEI President Marianne Rowden, has raised a number of challenging and very interesting questions that deserve longer answers. My brief responses follow.

Does multilateralism reflect globalization?

In the last half of the 1940s, when true multilateralism was born with the negotiation of the International Trade Organization (the ITO) and the creation of the GATT, multilateralism was the means envisaged to achieve globalization, at least an earlier form of globalization constrained as it was by the limited capacity at that time of war-damaged industrialized countries and poor former colonies. Later on, and up to the present, globalization has driven and is driving the need for improved multilateral agreements. While multilateral agreements enable globalization, they are not the primary driving force. Economic, technological and commercial, imperatives drive globalization to a greater extent than government policies or international agreements.

Are multilateral agreements contingent upon increased economic integration?

There is a mutuality between multilateral agreements and economic integration. Neither is the sole cause or the sole effect of the other. As one example: because there is an emerging global digital economy, there is a need for multilateral rules for e-commerce. When rules are put into place for e-commerce, they will foster the further expansion of participation in international trade.

Is it possible to achieve multilateral consensus on trade issues when countries are rethinking economic integration?

Current trade tensions and international competition viewed at a national level do not, in my view, bring an end to economic integration. Twenty-three countries are seeking entry into the WTO in order to achieve greater integration into the global economy. No Member of the existing 164 seeks to leave the WTO. Economic integration occurs due to economic forces that cannot be repealed nor fully countered. Thoughtful commentators believe that global supply chains will be reduced at the margin. To some extent they are likely to be reoriented. Just-in-time delivery is now seen to be subject to repeated disruptions. We have learned this during this year with the pandemic and over the last few years with trade hostilities and natural disasters. There is likely to be some pulling back in some areas and with some trading countries. But economic integration, viewed globally, will not end. The costs of retreating toward autarky are too great.

Multilateral trade agreements will always need to reflect current commercial realities as well as being designed to help shape a desired future. Multilateral rules are more, not less, necessary in current conditions.

How do international organizations channel member self-interest toward multilateral negotiations?

Members channel international organization agendas rather than the reverse. That said, the international organization, in my case, the WTO, has an obligation to provide members with the information needed to judge what international rules they need. The WTO provides transparency to Members’ officials as to the conditions of world trade and the measures, positive and negative, that Members apply that can affect their interests. The expertise of the WTO Secretariat is available to assist Members in crafting proposals for negotiation and to provide studies on request of issues of interest to members to enable them to consider what changes in the rules may be needed. The WTO, on behalf of its Members, has convening power to bring together institutions and experts that can address problems. One example is the challenge of restoring trade finance to meet the needs particularly of the WTO’s least developed Members.

What are the challenges to future multilateral negotiations?

- Global leadership by large economies — the United States, China or the EU

With respect to the immediate challenges posed by the pandemic it is the mid-sized countries such as Singapore, New Zealand, Canada, Korea and others who have been most active in making proposals. With respect to e-Commerce negotiations, it was Australia, Japan and Singapore that intiated the process, and then the EU, China and the United States joined. So leadership can come from a variety of WTO Members. That said, a fully multilateral agreement is unlikely to be reached absent participation of the largest economies. Two WTO agreements illustrate a challenge of a large Member not joining. Would expansion of either the Pharmaceutical Agreement or the Information Technology (ITA), both of which are zero tariff MFN (non-discriminatory) agreements be possible absent, in the case of the first, participation of the largest economies — for these purposes, including China and India? The same question can be posed with respect to any negotiations of disciplines on agricultural support, industrial subsidies, or fisheries subsidies. There must be cooperation of the largest trading members to reach comprehensive results. Even in the face of increased tensions in their trade relations, identifying areas of agreement cannot be precluded.

- Compelling problems to solve — digital services tax

As with a carbon tax, there is a lot of preparatory work to be done before an international negotiation can be considered. These future issues take time to consider. This was true before the first nontariff barrier and services agreements could be achieved. These subjects may at some stage come to the WTO for discussion, deliberation and negotiation, but that day may still be distant. These subjects are not on the current agenda. Work is likely to begin in other international fora

What are the prospects for future multilateral negotiations post COVID-19?

Measuring a trend requires choosing a base period and the scope of outcomes sought. There is no consensus at present among Members to have a major round of multilateral negotiations such as created the WTO in 1995 , nor had that question even been posed. That said, there are clear prospects for being above trend for achieving multilateral agreements compared with the the prior decade. The December 2017 WTO Ministerial Conference saw the launch of an increase in Member interest in reaching international agreements on a range of subjects. The Joint Initiatives created then are moving forward with support from WTO members accounting in each case for about three-quarters of global economic activity. The subjects include, for example, e- Commerce, domestic regulation of services, investment facilitation, and support for enhanced participation of micro and small to medium enterprises, as well as the empowerment of women in trade. Negotiations on fisheries subsidies show promise as well, more so than in the 20 prior years of negotiation.

Share

Share

Problems viewing this page? If so, please contact [email protected] giving details of the operating system and web browser you are using.