B. Health systems-related determinants of access

Key points |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There are different determinants of access and any lack of access to medicines or other medical technologies is rarely due entirely to a single determinant. The following sections discuss the main determinants of access that are linked to health, IP and trade.

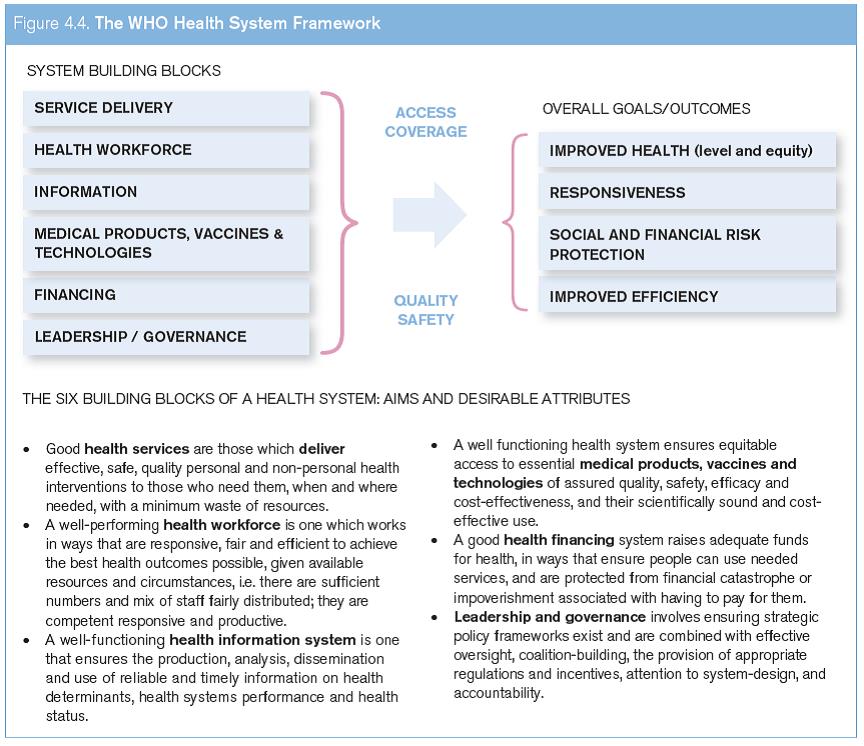

One overarching determinant for access to medical technologies is a well-functioning health system. A health system consists of all organizations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore or maintain health (WHO, 2000a). The WHO conceptualizes health systems in terms of six building blocks whose interplay helps in achieving desired health outcomes through ensuring universal coverage and equitable access to quality assured and safe health care (see Figure 4.4).

One important building block of any health system is equitable access to essential medical products of assured quality, safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness, and their scientifically sound and cost-effective use (WHO, 2007). All six building blocks of the health system are interdependent (see Figure 4.4).

This section describes some of the main health systems-related determinants of access to medicines and medical technologies. It explains the importance of measures to control medicine prices, in determining access and it demonstrates how taxes, duties and high mark-ups, when imposed on manufacturers' prices, can further result in unaffordability. Efficient public procurement can also ease access, as can, under certain conditions, local production and associated transfer of technology. The final segment in this section looks at regulation of medicines and medical technologies, and it explains why these are important aspects to ensure access to quality products.

Source: WHO (2007).

1. Generic medicines policies, price controls and reference pricing

Generic medicines policies which aim to increase the market share of cheaper generic medicines, control prices of medicines and regulate the level of medical expenses reimbursement are key policy interventions to control health budgets, and make medicines and other health products and services more affordable.

(a) Generic medicines policies

The use of generic medicines has been steadily rising not only in developing countries but also in developed countries as a result of economic pressure on health budgets. Many countries are using different measures to increase the market share of cheaper generics to control health budgets. Many of the current "blockbuster" drugs are nearing the end of their patent term and, over the next few years, it is to be expected that the market share of generics will continue to rise further.

Generic medicines policies can be divided into so-called supply-side and demand-side policies (King and Kanavos, 2002).

(i) Supply-side measures

Supply-side measures are primarily directed towards the specific health care system stakeholders that are responsible for medicine regulation, registration, competition (antitrust) policy, intellectual property rights (IPRs), pricing and reimbursement. Through such measures, policy-makers can impact the:

- speed with which a generic product is reviewed by the regulatory authority

- decision when to grant a patent through application of an appropriate definition of patentability criteria

- relationship between market authorization of medicines and patent protection (Bolar-exception and patent linkage)

- way clinical test data are protected from unfair competition

- ability of the originator to extend IP protection, for example through patent term extensions

- level of competition among manufacturers, and monitoring of agreements between originators and generic companies

- price(s) of generic product(s)

- reimbursement to the purchasers of medicine(s).

(ii) Demand-side measures

Generally, demand-side measures are directed at stakeholders such as health care professionals who prescribe medicines (usually physicians), people who dispense and/or sell medicines, and patients/consumers who ask for generic medicines. These measures usually relate to activities that occur after an originator loses market exclusivity and generic medicines have entered the market.

Through the use of appropriate demand-side measures policy-makers can impact the:

- prescribing of generic version(s) by physicians using the international nonproprietary name (INN)/generic name instead of the trade name

- dispensing of the generic version(s) by people who dispense and/or sell medicines

- confidence of prescribers, dispensers and consumers in the quality of generic medicines

- overall consumption pattern of the generic medicine(s) in the health care system

- demand by the consumer for generic products through higher co-payments for originator products

- perception of generic medicines (often patients agree that generics can help reduce costs, but many still prefer to take originator products).

Most of the policies in high-income countries work through a health insurance system, which has reimbursement procedures or requires higher co-payments, so as to incentivize consumers to choose generic medicines. The differences in contextual factors between high-income countries and LMICs that influence pro-generic medicines policies make it difficult to predict which policies can be successfully translated from high-income countries to LMICs.

Two enabling conditions may be needed before an LMIC can effectively implement pro-generic medicines policies:

- A mechanism to provide certainty that the generic medicines are of assured quality. This involves having an effective regulatory system, and possibly, a well-functioning trademark system.

- A robust supply of generic medicines to ensure the availability of assured quality, low-cost medicines.

The characteristics of the health care systems in many LMICs suggest that demand-side policies driven by consumers may be more important, as medicines are largely financed out-of-pocket and the selection of products purchased is made directly by consumers or patients without prescribers acting as intermediaries.

(b) Price control

There is potential for manufacturers to exploit market exclusivity when facing demand for medicines that remains relatively constant irrespective of changes in price (so-called "inelastic demand"). This has led many countries to regulate prices for at least some portion of the pharmaceutical market, most often patented products. Canada and Mexico, for example, have established price review regulation for on-patent pharmaceuticals, a move that is aimed at ensuring that prices paid by any section of the population, insured or not, are not excessive. In most other high-income countries, insurance coverage schemes require manufacturers to accept price limits in exchange for financing through reimbursement schemes.1

Various price control strategies have been used. These include, among others, controlling profits of manufacturers, direct price controls, comparing prices to internal or external references, constraining spending by physicians, enforcing prescription guidelines, tying marketing approval to prices, and placing limits on the promotion of medicines. Price control measures have also been subject to disputes in domestic jurisdictions.

Price controls can be applied either at the manufacturer, wholesaler or retailer level (see Box 4.4 for reference prices and price controls in Colombia). The most direct control method is when a government sets the sale price and prevents sales at any other price. Governments that enjoy some monopsonistic (i.e. where there is only one buyer) power may also directly negotiate favourable prices with manufacturers. The former method could be based on estimates of costs, which could be inaccurate, while the latter method may be more successful, depending on the degree of monopsony enjoyed by the government. Canada's Patented Medicines Prices Review Board protects interests of Canadian consumers by ensuring that the prices of patented medicines are not excessive. It reviews the prices that patentees charge for patented products in Canadian markets. If the Board considers a price excessive, it can order price reductions and/or the offset of excess revenues (see www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/).

Another method used by governments is to set an artificially low reimbursement price for a new drug, so that any price above must be borne by the patient. The reimbursement price then functions as the de facto market price. Finally, governments may regularly cut the reimbursement price of already existing marketed drugs. These types of price controls are market interventions, and controlled prices should allow for reasonable profits so as to avoid forcing needed suppliers out of the market.

Box 4.4. Reference prices and price controls in Colombia |

Colombia's National Medicines Pricing Commission fixes reference prices for all medicines commercialized in the country's public sector at least once a year. To do so, it takes into account the average price in the domestic market for a group of homogenous pharmaceutical products, i.e. products with identical composition, doses and formulas. If the price applied for such a medicine is above the reference price for homogenous products, direct price controls are applied and a maximum retail price is fixed by the Commission. |

Direct price controls are also applied if there are less than three homogenous products on the market. In such cases, the Commission establishes an international reference price (IRP) by comparing the price applied for the same product in at least three of eight selected countries from the region (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Peru and Uruguay) and in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. The lowest price found in any of these countries is fixed as the maximum retail price for Colombia. |

The application of price controls has played a prominent role in the case of lopinavir and ritonavir provided to HIV/ AIDS patients in Colombia. In 2009, the Colombian Ministry of Health rejected a 2008 application for a compulsory licence on the grounds of lack of public interest. As this medicine was listed on the national EML, its supply by insurers to patients was mandatory, and therefore the price applied by the right holder would not block access. At the same time, the Commission decided to regulate the price of the medicine concerned. The prices were fixed at US$ 1,067 for the public sector and US$ 1,591 for the private sector, representing an average reduction of between 54 per cent and 68 per cent per person per year (Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association, 2009). The right holder's appeal against the decision was rejected. In 2010, the originator company agreed to sell the medicine at the price fixed by the Commission. |

(c) Reference pricing

Reference pricing can determine, or be used for, negotiating the nationally regulated price or reimbursement level of a product based on the price(s) of a pharmaceutical product in other countries ("external") or relative to existing therapies in the same country ("internal"). Reference pricing typically controls the reimbursement level and thus is mainly useful in countries with insurance-based systems. This is seen as less restrictive than direct price controls.

(i) External reference pricing

International or external reference pricing is the practice of comparing the price(s) of a pharmaceutical product with the prices in a set of reference countries (Espin et al., 2011). Various methods can be used for selecting reference countries in the "basket" and for calculating external reference prices. There are also many ways to apply external reference pricing in practice. Box 4.4 describes how external reference pricing and prices controls work in Colombia.

(ii) Internal reference pricing

By contrast, internal reference pricing compares the same or similar medicines in the same country. Medicines to be compared are classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) system, which compares medicines at five levels, from the organ or system on which the drug works through to the chemical structure (ATC 5 level).2 Internal reference pricing is "the practice of using the price(s) of identical medicines (ATC 5 level) or similar products (ATC 4 level) or even with therapeutic equivalent treatment (not necessarily a medicine) in a country" to determine a price.3 Internal reference pricing is particularly effective when considering the pricing of originator products, which contain the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) as generic versions, but are typically more expensive.

(d) Health technology assessments

In the past years, an increasing number of countries have started to introduce pay-for-performance schemes based on health technology assessments that evaluate the medical benefits and the cost-effectiveness of a treatment as a tool to contain costs and to direct expenditure to improved health outcomes (Kanavos et al., 2010).

Assessing health technologies is a multidisciplinary process: information about the medical, social, economic and ethical issues relating to the use of a health technology is gathered in a systematic, transparent and unbiased manner, so as to inform the formulation of safe, effective health policies that are patient-focused and that seek to achieve best value.4 A health technology assessment of a medicine, or of a medical device or a clinical or surgical procedure, therefore not only examines its safety, efficacy or effectiveness, but also undertakes a cost-benefit analysis and evaluates various other aspects of the use of a medical product or technology. While healthtechnology assessments can differ widely, cost-benefit analyses focus on clinical effectiveness – a comparison of health outcomes of alternative technologies with available alternatives – and on cost-effectiveness – comparing improvements in health outcomes with the additional costs of the technology. The latter comparison enables a determination as to whether the costs are proportionate to the health outcomes, and thus whether the medical product should be provided to the patient (for more information, see Garrido et al., 2008). To what extent such health technology assessments will contribute to control health expenditures in the long term cannot be fully assessed yet.

(e) Volume limitations

Governments may also impose volume limitations to control the quantity of a new drug that may be sold. France imposes price-volume agreements on manufacturers of new medicines (OECD, 2008). A "price-volume" agreement links the reimbursement price of a new drug to a volume sales threshold. If the threshold is exceeded, the manufacturer must provide compensation through price reduction or cash payments to the government (depending on the country) or remove the product from the market. Through such volume limitations the payer can control the maximum cost implications of the introduction of new, expensive treatments and limit the incentive for companies to promote a wide use of new expensive treatments.

2. Differential pricing strategies

Differential pricing (also known as "tiered pricing" or "price discrimination") occurs when companies charge different prices for the same product depending on the different classes of purchasers, and where such price differences cannot be explained by differences in the cost of production. Price differentials may exist across different geographical areas or according to differences in purchasing power and socio-economic segments. Because differential pricing involves the division of markets into different tiers or groups, the practice is also known as tiered pricing. Such price discrimination is only feasible to the extent that markets can be effectively segmented, in order to prevent arbitrage (the purchase of products in the lower-price market and subsequent sale in the higher-price market).

Tiered pricing can be practised in different ways. Private companies can negotiate individual agreements with other companies. They can also negotiate price discounts with governments or through regional or global bulk purchasing arrangements and the licensing of production for specified markets. Creating market segmentation can be achieved through various marketing strategies (e.g. using different trademarks, license agreements, dosage forms or presentation of products), by having more stringent supply chain management by purchasers, and by having import controls in high-income countries and export controls in poorer countries (see Box 4.5 for differential packaging as another example to support differential pricing strategies). Differential pricing can, in principle, make medicines more affordable to larger segments of the population and could also lead to increased sales, thus benefiting pharmaceutical manufacturers (Yadav, 2010).

However, it reaches its limits where the affordability level of patients is less than the marginal cost of manufacturing. Differential pricing can thus only be a complementary policy, whereas continuing government commitment to provide access to medicines to the poor is essential (Yadav, 2010).

Companies are sometimes reluctant to follow tiered pricing strategies. A possible reason is fear of price erosion in high-income markets as a result of arbitrage. Companies may also be reluctant to provide differential prices to middle-income countries, as it may be difficult for them to preserve higher prices in neighbouring markets or in countries with a similar income level.

The ability to differentiate within countries according to socio-economic segments of the population, and also to differentiate between the public and private sectors, might serve to overcome these difficulties. Preventing lower priced products from flowing back to high-income private markets will remain a challenge, but the trend may be changing. Box 4.5 presents an example on how differential packaging can be used to separate markets. Recently, a number of research-based companies have run pilot programmes extending differential pricing, including intra-country differential pricing, to emerging economies. They have also expanded these programmes to encompass a broader range of medicines, including cancer medicines and biologicals.5 This shows that companies are working to adapt their current single global price model to the socioeconomic reality in emerging economies, thus basing their business model on a different volume to price equation.

Box 4.5. Differential packaging

|

In 2001, as part of the Memorandum of Understanding between the WHO and Novartis to make available artemetherlumefantrine at cost price for use in the public sector of malaria-endemic countries, Novartis developed differential packaging for artemether-lumefantrine destined for the public sector. This differed from the existing packaging for products destined for the private sector. The WHO collaborated with the company to develop four different courseof-therapy packs (for four separate age groups), each containing pictorial diagrams on how to take the medicines and all aimed at improving adherence to treatment among illiterate population groups. Initially, packs were made available to WHO procurement services. They were subsequently made available to UNICEF and, progressively, to additional procurement services supplying the public sector only. The leakage of such packs from the public sector into the private sector is not significant. The use of a distinctive "Green Leaf" logo on the packs facilitates the process of tracking and monitoring of availability and market share at point of sale. |

One example of differential pricing is the Accelerating Access Initiative, a partnership established in May 2000. Among five UN organizations (UNAIDS, UNICEF, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the World Bank and the WHO) and five pharmaceutical companies. The objective was to address the lack of affordable HIV medicines and of HIV/AIDS care in selected developing countries (WHO/UNAIDS, 2002). The pharmaceutical companies involved agreed to either donate medicines and/or provide significant cost reductions.

Differential pricing is already well established in the vaccine market. A three-tiered pricing structure is used for most vaccines sold in both developed and developing countries. Companies charge the highest prices in high-income countries, low prices in countries prioritised by the GAVI Alliance, and intermediate prices in middle-income countries. Vaccines are also the sector where differential pricing is more widespread within a country: for example, one company offers its hepatitis B vaccine at two different prices within India, with the public sector only paying about half the price paid by the private sector.

3. Taxes

While medicines are often subject to indirect taxes such as a purchase tax, sales tax or VAT, entities producing and selling medicines may also be subject to direct taxes on the revenue generated (e.g. corporate income tax). Taxes add up to the end-price paid by the consumer and is, therefore, a factor that affects access to medicines.

In 2010, the VAT rate on medicines in high-income countries was between zero and 25 per cent, with Australia, Japan and the Republic of Korea having a tax exemption policy. Similarly, countries such as Colombia, Ethiopia, the State of Kuwait, Malaysia, Nicaragua, Oman, Pakistan, Uganda and Ukraine reported zero VAT and sales tax on medicines. In LMICs that charged taxes on medicines, the tax rate ranged from 5 per cent to about 34 per cent. In some LMICs, the situation in relation to taxation of medicines is even more complex and variable, sometimes with multiple federal and state taxes being applied. Furthermore, imported and locally made medicines are sometimes taxed differently. The study concludes that domestic taxes such as VAT or sales tax are often the third largest component in the final price of a medicine (Creese, 2011).

Certain practical tax measures can be used to reduce the price of medicines (the Peruvian experience with tax exemption measures is set out in Box 4.6). One such measure is to remove taxes on medicines that have relatively inelastic demand patterns (i.e. people will buy these medicines regardless of their price). For example, Mongolia removed taxes on imported omeprazole sold in private pharmacies, a move that led to a price fall of between US$ 5.91 and US$ 4.85 for a 30-capsule pack, while the Philippines removed 12-per-cent VAT thus reducing the price of a pack of ten generic co-trimoxazole tablets (480 mg) from 14.90 pesos to 13.30 pesos (Creese, 2011).

Another measure that may improve access to medicines is alterations in tax rates. It should be possible to evaluate the consequences of defined changes in tax rates that either improve or reduce access to medicines, and then propose tax policy changes accordingly. In 2004, Kyrgyzstan reduced VAT and regional sales tax on medicines, while in Pakistan, following a successful consumer advocacy challenge, the 15-per-cent sales tax on medicines was removed altogether. Although alterations in tax rates may not occur until there is a change in national tax regimes, the impact of this measure may be substantial (Creese, 2011). Removing customs duties discussed later in this chapter is a similar measure that can have a direct bearing on prices and access. In both cases, however, it is important to ensure that savings due to reduced taxes or custom duties are passed on to the consumer, since this is not always the case, as can be seen from the example of Peru (see Box 4.6).

Box 4.6. Peru: tax exemption measures for cancer/diabetes treatment drugs |

In 2010 and 2011, Peru carried out two studies on the impact of tax exemption measures on the price of certain cancer and diabetes medicines. In 75 per cent of the 40 diabetes medicines in the retail sector examined as part of the studies, companies had not passed on possible price reductions resulting from the introduction of tax exemption measures. In the public sector, prices for 44 per cent of the medicines examined did not reflect the potential benefits accruing from tax exemption measures, whereas 56 per cent partially reflected such measures in the form of price reductions. For medicines not subject to competition, prices either did not vary, or were subject to large variations (up to 248 per cent), depending on the volume purchased. |

Of the five cancer treatments examined which were marketed in the retail sector before and after the introduction of tax exemption measures, prices decreased in two cases, but did not change in the case of three other retail prices (i.e. the benefit due as a result of the introduction of tax exemption measures was not passed on). |

In the public sector, prices were evaluated for eight medicines before and after tax exemption measures. In the case of four medicines, companies had not passed on the tax exemption in the form of reduced prices. By contrast, prices decreased for the other four medicines examined. Following the introduction of tax exemption measures, prices remained stable for the six drugs for which there was no competition. Prices decreased in the case of the two drugs for which there were alternatives on the market. In one of these cases, the price reduction was up to 38 per cent.6 |

The reduction or elimination of taxes on medicines may also be coupled with the increase in, or introduction of, taxes on public health "bads" (i.e. tobacco, alcohol and unhealthy food). Advocates of this approach often argue that the funds raised from taxes on unhealthy consumption patterns and behaviours can easily balance out, or sometimes surpass, revenue losses due to the reduction or elimination of taxes on medicines, leaving both government and individuals better off (Creese, 2011). In their view, this approach would therefore offer the potential of linking significant revenue gains with improved access to medicines.

4. Mark-ups

A mark-up represents the add-on charges and costs applied by different stakeholders in the supply chain in order to recover overhead costs and distribution charges, and make a profit. The price of a medicine includes mark-ups that have been added along its supply chain distribution. Medicine mark-ups can be added by manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, pharmacists and many others who play a role in the supply chain distribution (Ball, 2011). Like taxes, a mark-up also contributes to the price of medicines and thus has a direct bearing on access to medicines.

Mark-ups, including those charged by wholesalers and retailers, are common in medicine supply chain distributions in both the public and private sectors. For example, a secondary analysis of WHO/Health Action International (HAI) surveys of developing countries indicates that wholesale mark-ups ranged from 2 per cent in one country to a combined mark-up by importers, distributors, and wholesalers of 380 per cent in another country (Cameron et al., 2009). In addition, a secondary analysis of WHO/ HAI surveys indicates that there is huge variability in the cumulative percentage mark-ups (i.e. all mark-ups added from manufacturer's selling price to final patient price) between the public and private sectors (Cameron et al., 2009). Mark-ups on medicines can also vary depending on the type of medicine (i.e. originator versus generic). Without appropriate regulation of mark-ups, there can be significant elevation of the consumer price, and, consequently, a substantial impact on access to medicines.

In high-income countries, mark-up regulation in medicine supply chain distributions is usually part of a comprehensive pricing strategy that also addresses medicine reimbursement (Ball, 2011). There is little data on mark-up regulation in the pharmaceutical supply chain in LMICs. WHO pharmaceutical indicator survey data show that around 60 per cent of low-income countries report regulating wholesale or retail mark-ups. In middle-income countries, regulation in the public sector is at a comparable level (Ball, 2011).

Mark-up regulation can positively impact access to medicines, but may also have some adverse effects (Ball, 2011). Because mark-up regulation reduces margins for businesses, some medicines may no longer be offered, or may be offered in reduced quantities, thus adversely affecting product availability and price competition.

5. Effective and efficient procurement mechanisms

Effective procurement of medical products requires the systematic coordination of business operations, information technology, quality assurance, safety and risk management, and legal systems. Furthermore, it is important to be able to contain costs through regular review of procurement models and approaches, monitoring of prices, and record-keeping, in order to make informed decisions (Ombaka, 2009).

(a) Principles for effective procurement

Procurement systems are designed to obtain the selected medicines and products of good quality, at the right time, in the required quantities, and at favourable costs. The WHO has developed a series of operational principles in procurement systems, the purpose of which is to increase access through lower prices and uninterrupted supply (WHO, 2001c). These principles are:

- Divide different procurement functions and responsibilities (selection, quantification, product specification, pre-selection of suppliers and adjudication of tenders) among multiple parties and give each one of them the necessary expertise and resources to do their particular job.

- Ensure transparency of procurement and tender procedures, follow written procedures throughout, and use explicit criteria to award contracts.

- Provide for a reliable management information system that functions to plan, and monitor procurement on a regular basis, including through the execution of an annual external audit.

- Limit public-sector procurement to an essential drugs list or national/local formulary list so as to ensure that the necessary products are procured.

- List drugs by their INN/generic name, on procurement and tender documents.

- Quantify procurement orders based on past consumption, provided that such data have been proven to be accurate. Consumption data must be updated continually, in order to take into account changes in morbidity, and factors such as seasonality and prescribing patterns.

- Finance procurement using reliable mechanisms, such as decentralized drug purchasing accounts or revolving drug funds. In each case, the mechanism itself must also be adequately funded.

- Purchase the largest appropriate quantity in order to achieve economies of scale.

- Obtain favourable prices without compromising quality when procuring for the public sector.

- Monitor this process of procurement where prices are negotiated centrally but ordering done by individual health facilities in the periphery.

- Pre-qualification of possible suppliers is essential, and criteria such as product quality, reliability of service, time for delivery and financial sustainability should be considered.

- Assured quality of purchased medicines, according to international standards.

Parties to the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement are also bound to provide for competitive, non-discriminatory and transparent tendering for a range of public procurement in the health sector. Further guidance on how to organize efficient procurement of medical technologies can be obtained from different sources. The World Health Organization Good Governance for Medicines programme offers a technical support package for tackling unethical issues in the public pharmaceutical sector (WHO, 2010d). The WHO has developed a model quality assurance system for procurement agencies (WHO, 2006a). The World Bank has prepared guidelines containing standard bidding documents and a technical note for use by implementing agencies procuring health-sector goods through international competitive bidding.7 For the purpose of combating HIV/ AIDS, these guidelines have been adapted in a separate decision maker's guide.8

(b) Procurement and patent information

Procurement systems should be designed to obtain selected medicines and other medical products of good quality, at the right time, in the required quantities, and at favourable costs. While generally the supplier is responsible for ensuring that all necessary rights to products, including IPRs, have been secured in accordance with the specifications in tender documents and procurement contracts, procurement agencies also have to consider the patent status of products early in the procurement process. Checking the validity of patents, price or licence negotiations with the patent holder and the possible use of compulsory licences or government use by the respective government takes time. Therefore, if this information is only gathered at a late stage of the procurement process, delays in the procurement can lead to stock outs. The content and sources of patent information is further explained in Chapter II, Section B.1(b)(viii). This was also the subject of a WHO/WIPO/ WTO joint technical symposium entitled "Access to Medicines, Patent Information and Freedom to Operate", held in February 2011.9

(c) Pooled procurement

Pooled procurement, also known as "group purchasing" or "bulk purchasing" has been defined as "purchasing done by one procurement office on behalf of a group of facilities, health systems or countries" (MSH, 2012). Pooled procurement is a strategy that can make medicines more affordable and that can help resolving challenges such as poor quality, and other bottlenecks generally associated with procurement and supply chains of essential medicines.

Economies of scale and long-term prospects of supply, which are prevalent in most public-sector procurement systems, enable suppliers to lower their prices. Pooled procurement in the health sector occurs in one form or another in both developed and developing countries. Both the public sector and private sector (e.g. a group of private hospitals sharing a joint procurement system) use those mechanisms at various levels of scale. In high-income countries, large insurance and reimbursement systems support the purchase of medicines and other medical technologies that are acquired through pooled procurement. LMICs now increasingly adopt joint purchasing practices. Current programmes in India and China to expand health care to their large populations are examples of this phenomenon. In public-sector procurement, most countries benefit from the advantages of central bulk procurement. Many low-income countries have established central procurement agencies to manage the pooled needs of the health care system. With the leverage of larger orders, they can achieve economies of scale and negotiate best prices. Fully functioning pooled procurement systems contribute to the development of quality control systems, promote the improvement of storage and delivery infrastructure to accommodate large quantities of medicines and other health technologies.

Successful pooled procurement schemes have reported substantial reductions in the unit price of medicines. Some well-known examples include the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Strategic Fund for Essential Public Health Supplies, the PAHO Strategic Fund for Vaccines, the African Association of Central Medical Stores, andthe Group Purchasing Program of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GPP/GCC). The OECS, a self-financing public-sector monopsony, has consistently reported substantial reductions in the unit price of medicines. In 2001–2002, an annual survey of 20 popular drugs available in the OECS region, found that prices under the pooled procurement scheme of the OECS were 44 per cent lower than individual country prices (OECS, 2001). The GPP/GCC also experienced that improved procurement can reduce costs and enhance the efficiency of health service. The PAHO Strategic Fund is another example of pooled procurement. The Fund was developed by the PAHO Secretariat at the request of member states. Currently, 23 PAHO member states participate in this strategic fund, which was created to promote access to quality, essential public health supplies in the Americas. The Global Fund employs the Voluntary Pooled Procurement as a cost-effective way of ensuring efficient procurement of ARVs, rapid diagnostic kits for HIV and malaria, Artemisininbased combination therapies and long-lasting insecticidal nets (Global Fund, 2010a; 2010b).

6. Local production and technology transfer

Most countries import medicines, diagnostics, vaccines and other medical products from the global market. Nevertheless, a number of LMICs aspire to build and strengthen their domestic medical products industry. Trends show that local production is growing and diversifying in some of these countries.10 However, the evidence that local production results in increased access to medical products is inconclusive (WHO, 2011g).

In order to become economically viable, local producers, particularly those based in low-income countries, have to address a number of challenges. These challenges may include:

- weak physical infrastructure

- scarcity of appropriately trained technical staff

- dependence on imported raw materials, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)

- weak and uncertain markets

- lack of economies of scale

- high import duties and taxes

- lack of a conducive policy environment and policy coherence across sectors

- weak quality control and regulation measures

- existence of patents on key products or technologies

- later regulatory clearance due to data exclusivity rules, where recognized.

Overcoming these challenges can add to the cost of production, thus making the product relatively uncompetitive in comparison with cheaper imports. According to Kaplan and Laing (2005), "local production of medicines at higher cost than equivalent imports may have no impact whatsoever on patient access to needed medicines".

The framework diagram depicted in Figure 4.5 outlines the main relevant factors from both an industrial policy (Box A) and a public health policy (Box B) perspective. It indicates that common or shared goals exist between these two perspectives, such that the objectives of industrial policy can also help to meet those of public health (Box C). The government's role is to provide a range of direct and indirect financial incentives and to help ensure coherence across the entire policy arena (Box D).

It is important that any incentives for local production are not just aimed at increasing industrial development per se. A good example is the WHO technology transfer for pandemic influenza vaccines and enabling technologies described in Box 4.7. They should also explicitly aim to improve people's access to locally produced medical products. To achieve this, it is important that government incentives are designed to support the shared goals of industrial policies and health policies, for example, by strengthening an effective national regulatory authority. The WHO guidelines on transfer of technology in pharmaceutical manufacturing provide useful guidance in this area.11

Currently, the TRIPS Agreement transitional period, within which least-developed countries (LDCs) are not required to grant and enforce pharmaceutical patents up to 2016, could provide opportunities to set up local production in LDCs for products that are still under patent protection in other countries.12

Some existing technology transfer projects are designed to involve LDCs in local and regional manufacturing initiatives through collaborations with private companies and national governments. One such initiative is a joint venture between an Indian generic manufacturer and a Ugandan company. Under this programme, Indian experts provide training to local staff. This partnership resulted in the establishment of a manufacturing plant near Kampala to produce ARV medicines and antimalarials. The plant has been certified by the WHO as compliant with good manufacturing practices (GMPs) and has obtained WHO pre-qualification for two products.

The Brazilian government is cooperating with the Mozambique Ministry of Health to establish Mozambique's first manufacturing facility for the production of first-line ARV medicines, based on the portfolio of drugs produced by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. 2011 saw the signing of an agreement to construct the facility. As part of this agreement, Brazil will supply equipment and training for local technicians working in the facility.

Source: WHO (2011g).

Box 4.7. WHO technology transfer for pandemic influenza vaccines and enabling technologies |

The WHO Global Pandemic Influenza Action Plan, published in 2006, identified the construction of new influenza vaccine production plants in developing countries as a priority, so as to increase global capacity and pandemic preparedness.13 The WHO has provided seed funding to 14 vaccine manufacturers in Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kazakhstan, the Republic of Korea, Mexico, Romania, Serbia, South Africa, Thailand and Viet Nam to enable domestic production. |

The classical methods of manufacturing influenza vaccine, such as the 1940s vintage hen egg-derived technology that still accounts for the bulk of influenza vaccine production, are not protected by IPRs. A central technology transfer hub was established in the Netherlands, thereby concentrating expertise in a single location from which technology transfer to multiple recipients could be carried out efficiently. Personnel from the majority of the countries who provided funding for the project, as well as personnel from national regulatory agencies, have received training at this technology transfer hub (Hendriks et al., 2011). |

Enabling technologies |

Live attenuated influenza vaccine technology: Several of the manufacturers opted to use the live attenuated influenza vaccine technology, which produces a high-yield, low-cost vaccine that is easy to administer. In order to facilitate access to the know-how, clinical data and seed strains required for this technology, the WHO, on behalf of developing country vaccine manufacturers, negotiated and acquired a transferable non-exclusive licence. Sub-licences were granted to three developing country vaccine manufacturers. |

Adjuvant technology: Adjuvants have been shown to permit dose-sparing for pandemic influenza vaccines, and thus multiply capacity, enabling a larger number of people to be immunized. However, the know-how on these adjuvants has been predominantly in the hands of a few multinational vaccine manufacturers. The WHO determined that the IPRs on one of the lead adjuvants had limited geographical scope, and therefore could be produced in developing countries. To transfer the necessary know-how on how to produce the adjuvant, the WHO facilitated the establishment of an adjuvant technology transfer hub at the University of Lausanne. The hub established production processes for the adjuvant, and has already successfully transferred the technology to Indonesia and Viet Nam. |

In 2012, the South African government, through a South African company, entered into a joint venture with a Swiss company to establish the first pharmaceutical plant to manufacture APIs for ARV medicines in South Africa. This will involve the construction of a new facility in South Africa designed to develop locally mined fluorspar into higher value fluorochemical products. The project is aimed at reducing South Africa's dependence on imported drugs and enabling the manufacture of ARV medicines from locally sourced and produced APIs.

7. Regulatory mechanisms and access to medical technologies

This section builds on Chapter II, Section A.6, and focuses on the WHO Prequalification Programme, the role of global donors in regulatory standards harmonization, complex supply and management systems, and the problem of substandard and spurious/falsely-labelled/falsified/counterfeit (SFFC) products.

Regulation of medical technologies plays a key role in determining access to quality-assured medical products. While certain positive developments have taken place in recent years, regulatory control for medicines and medical technologies in LMICs needs to improve further. The WHO works with its member states in assessing national regulatory systems to identify gaps, develop strategies for improvement and support countries in their commitment to build national regulatory capacity. WHO (2010c) provides an overview of the regulatory situation in Africa (see Box 4.8).

(a) The Prequalification Programme

The Prequalification Programme, a UN initiative managed by the WHO, has contributed substantially to improving access to quality medicines in developing countries through ensuring compliance with quality standards (see Box 4.8). The programme aims to facilitate access to medical technologies that meet international standards of quality, safety and efficacy. It extends to medicines used for HIV/ AIDS, TB, malaria, reproductive health and influenza as well as vaccines and diagnostics.14

Box 4.8. WHO assessment of medicines regulatory systems in sub-Saharan African countries |

A recent WHO report synthesizes the findings of assessments carried out on national medicines regulatory authorities in 26 African countries over an eight-year period and provides an overview of the regulatory situation in Africa (WHO, 2010c). |

The report concluded that while structures for medicines regulation existed, and while the main regulatory functions were being addressed, in practice, the measures were often inadequate. Common weaknesses included fragmented laws in need of consolidation, weak management structures and processes, and a severe lack of staff and resources. On the whole, countries did not have the capacity to control the quality, safety and efficacy of the medicines circulating in their markets or passing through their territories. |

The WHO recommends that regulatory capacity in African countries be strengthened, using the following approaches: |

|

|

|

|

The Prequalification Programme does not replace national regulatory authorities or national authorization systems for the importation of medical technologies. If a product meets the specified requirements, and if the manufacturing site complies with current GMP, both the product linked to a specific manufacturing site and details of the product manufacturer are added to a list of pre-qualified medicinal products. This list is published by the WHO on a publicly accessible website.15

WHO pre-qualification is a recognized quality standard that is used and referred to by many international donors and procurement agencies.

(b) Regulation of medical devices

Medical devices include a wide range of tools – from the simple wooden tongue depressor and stethoscope to the most sophisticated implants and medical imaging apparatus. As is the case with vaccines and medicines, governments need to put in place policies that ensure access to quality, affordable medical devices, and also ensure their safe and appropriate use and disposal. Therefore, strong regulatory systems are needed so as to ensure the safety, effectiveness and performance of medical devices. A recent example for this need is the use of non-medical grade silicone in breast implants manufactured by a company based in France (see Box 4.9). In general, medical devices are submitted to regulatory controls and, consequently, most countries have an authority that is responsible for implementing and enforcing specific product regulations for medical devices.16 This also holds true for LMICs where more than 70 regulatory control authorities are in place (WHO, 2010a). Conversely, many other LMICs still do not have an authority responsible for implementing and enforcing medical device regulations. Implementation and enforcement are complicated, due to shortages of professional biomedical engineers, lack of harmonization in medical devices procedures and limited information. National guidelines, policies or recommendations on the procurement of medical devices are not used in a majority of countries, either because they are not available or because there is no recognized authority in place to implement them. This creates challenges to establish priorities in the selection of medical devices on the basis of their impact on the burden of disease. The lack of regulatory authorities, regulations and lack of enforcement of existing regulations has a negative impact on access to quality products. The WHO has published a global overview and guiding principles on medical device regulations to assist countries in establishing appropriate regulatory systems for medical devices (WHO, 2003a).

Box 4.9. Europe: tightening the control to guarantee the safety of medical devices |

The EU legal framework relating to the safety and performance of medical devices was harmonized in the 1990s.17 Under this legislation, medical devices are subject to strict pre-market controls by independent assessment bodies (notified bodies), which review the manufacturer's design and safety data for the product. Despite such control mechanisms, non-medical grade silicone was used in breast implants manufactured by a company based in France, thereby resulting in an unusually high short-term rupture rate of these breast implants. Incidents such as this highlight the need to modernize and strengthen the EU legislation that applies to medical devices. In February 2012, the European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Policy announced the imminent completion of the revision of the relevant legislation, based on the identification of shortcomings in the current laws. The Commissioner has also called on EU member states to immediately tighten controls and increase surveillance (European Commission, 2012). |

(c) Role of global donors in regulatory standards harmonization

Increasingly, major donors and donor programmes such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and UNITAID are financing major procurement programmes to increase access to medicines, with a specific focus on the major infectious diseases HIV/ AIDS, malaria and TB. Donors demand compliance with certain quality standards, often by way of reference to the Prequalification Programme and WHO quality standards. The donor community and the NGO community use WHO pre-qualified quality control laboratories for quality control analysis of the procured products, and such laboratories are becoming increasingly available in all WHO regions. Donors have also started to commit funds aimed at ensuring that national quality assurance systems are put in place, and several donors have directed funding towards regulatory capacity-building in the receiving countries. Although significant progress has been made, the quality assurance policies of programmes such as the Global Fund, PEPFAR, UNITAID, UNFPA, the Global Drug Facility and UNICEF are not yet fully aligned. Given the extent of these programmes and the dominant role they play in the procurement of HIV/ AIDS, malaria and TB medicines, diverging requirements for quality and safety can lead to market distortions, as different conditions need to be fulfilled for different purchasers. The creation of a single competitive market would represent an important contribution to the process of enabling access to good quality, affordable medicines.

(d) Complex supply and management systems

One of the main regulatory determinants that are also linked to international trade is the increasing fragmentation of global supply chains. In order to lower costs, many manufacturers have in the past outsourced basic research and production of, for example, APIs and medical device components to countries such as China, India and the Republic of Korea. As a result, growing trade in the products between continents creates a more complex supply chain, challenging the regulatory agencies that need to survey the complete supply chain, so as to ensure that end products meet the required quality standards.

A finished pharmaceutical dosage form or medical device may have been assembled using materials sourced or outsourced from many different parts of the world. In the case of the United States, for example, 80 per cent of APIs and 40 per cent of finished product medicines are imported from other countries (Institute of Medicine, 2012).

One of the hazards of purchasing ingredients for medicines or parts for a medical device from abroad is that it is more difficult to inspect the various elements of the long and complex supply chain. For example, a company that has received GMP certification to supply APIs from a stringent regulatory authority may also purchase APIs from other manufacturers who have not been certified. Furthermore, the large number of parties who may be involved in API production can result in a situation where manufacturing sites change, thus creating risks for process and method transfer-related issues.

(e) Substandard and spurious/falselylabelled/falsified/counterfeit medical products: a global concern

The steady increase in the production, sale and use of substandard and SFFC medical products poses serious public health problems. Medical products that do not meet quality standards, and contain either none or the wrong doses of active ingredients or different substances, result in therapeutic failure, exacerbation of disease, resistance to medicines and even death. Although the number of reported cases of substandard and SFFC medical products continues to rise, the exact magnitude of the problem is unknown, as the diversity of information sources makes compiling statistics a challenge.18

Box 4.10. Terminology: substandard medicines and counterfeits |

A multitude of terms is used in the debate on substandard and counterfeit medical products, sometimes giving different meanings to the same term. How these terms are used and defined is of particular relevance for the adoption and application of sound and acceptable measures to combat the proliferation of substandard and counterfeit medical products (Clift, 2010). In 2010, the WHO carried out a survey in 60 member states which was aimed at ascertaining information about the various terms and definitions used in these countries' respective national laws.19 The findings showed that the legal definition of counterfeit differs widely in various national contexts. |

Substandard medicines: "Substandard medicines are pharmaceutical products that fail to meet either their quality standards or their specifications, or both. Each pharmaceutical product that a manufacturer produces has to comply with quality assurance standards and specifications, at release and throughout its shelf-life, according to the requirements of the territory of use. Normally, these standards and specifications are reviewed, assessed and approved by the applicable national or regional medicines regulatory authority before the product is authorized for marketing".20 |

SFFC medicines are deliberately and fraudulently mislabelled with respect to identity and/or source. The source of SFFC medicines is therefore usually unknown and their content unreliable. SFFC medicines may include products with the correct ingredients or with the wrong ingredients, without active ingredients, with insufficient or too much active ingredient, or with fake packaging.21 |

The TRIPS Agreement defines "counterfeit" in relation to trademarks in a general manner, not specific to the public health sector. According to footnote 14(a) to Article 51 of the TRIPS Agreement: "Counterfeit trademark goods' shall mean any goods, including packaging, bearing without authorization a trademark which is identical to the trademark validly registered in respect of such goods, or which cannot be distinguished in its essential aspects from such a trademark, and which thereby infringes the rights of the owner of the trademark in question under the law of the country of importation". Counterfeiting is thus limited to goods using identical or similar trademarks without authorization of the trademark owner. It generally entails slavish copying of the protected trademark. Given the intended confusion between the genuine product and the copy, fraud is usually involved. However, the use of the term "counterfeit" in practice seems to have diverged from this narrow meaning in a number of WTO members, where it encompasses other forms and categories of IPR infringement. |

(i) What are we talking about?

While the terms "spurious, falsely-labelled, falsified and counterfeit" are used in public health debates to describe the same problem of deliberately mislabelled medicines with respect to their identity and/or source, substandard medicines are medicines that do not meet the required quality standards. A brief summary of the main terms used to describe substandard and counterfeit medical products is provided in Box 4.10. While both phenomena constitute a threat to public health, it is important to distinguish between the two, as to different measures are needed and different actors need to be involved to effectively fight against them.

(ii) What is the problem?

All types of medicines, including both originator and generic products, are subject to counterfeiting – from medicines for the treatment of life-threatening conditions to inexpensive generic versions of painkillers and antihistamines. The ingredients found in such products may range from random mixtures of harmful toxic substances to inactive, ineffective preparations. Some products contain a declared, active ingredient and look so similar to the genuine product that they deceive health professionals as well as patients. Substandard and SFFC products are always illegal.22

The nature of the problem of substandard and SFFC products is different in different settings. In some countries, especially in developed countries, expensive hormones, steroids, anticancer medicines and lifestyle drugs account for the majority of products sold – often by way of Internet-based transactions. In other countries, SFFC products often relate to inexpensive medicines, including generic medicines.

In developing countries, the most disturbing trend is the prevalence of substandard and SFFC medical products for the treatment of life-threatening conditions such as malaria, TB and HIV/AIDS (see Box 4.11 for the quality of antimalarials in sub-Saharan African countries). Experience has shown that vulnerable patient groups who pay for medicines out of their own pockets are often the most affected by the negative impacts of substandard and SFFC products (WHO, 2011h).

Substandard and SFFC medicines are found everywhere in the world, but are typically a much greater problem in regions where regulatory and enforcement systems for medicines are weakest. In industrialized countries with effective regulatory systems and market control, the incidence of these medicines is very low – less than one per cent of market value, according to the estimates of the countries concerned.23

The prime motivation for the production and distribution of substandard and SFFC medical products is the potentially huge profits. A number of factors favour their production and circulation, including:

- a lack of equitable access to and affordability of essential medicines

- the presence of outlets for unregulated medicines

- a lack of appropriate legislation

- absence or weakness of national medicines regulatory authorities

- inadequate enforcement of existing legislation

- complex supply chains

- weak criminal sanctions (WHO, 2011h).

(iii) How to combat substandard and SFFC medical products?

Combating substandard and SFFC medical products forms part of the work of regulatory agencies, but other law enforcement agencies are also involved in this area (seeChapter II, Section B.1(f)). In most countries, regulatory authorities can take measures against substandard and SFFC medicines and their manufacturers. In the case of substandard medicines, the identity of the producer is known and the problem lies in non-compliance with GMP standards. Counterfeiters, on the other hand, usually work in unauthorized settings with the intention of hiding their identity. This means that enforcement measures taken by national and regional regulatory procedures may be only partially successful. Thus, the standard regulatory approach for legally manufactured but substandard medicines cannot be successful on its own. To effectively combat SFFC medicines, other measures such as border controls and criminal prosecution need to play a greater role. In addition, measures need to be adapted to the situation in each individual country. Border controls may be effective if products are imported. They are particularly relevant because, increasingly, substandard and SFFC medicines are imported. In countries where SFFC products are manufactured locally, the emphasis needs to be placed on identifying and prosecuting the local manufacturers of these products. There is, therefore, a need for collaboration both at national and international level between various government institutions, including legislative bodies, relevant enforcement agencies and the courts (WHO, 2011h).

Box 4.11. WHO survey of the quality of selected antimalarials in six countries in sub-Saharan Africa |

The six countries involved in this WHO survey (Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania) have been supported in the past by the WHO with specific measures designed to strengthen their regulatory controls over antimalarial products. Of the 267 samples fully tested, 28.5 per cent of failed to comply with specifications. This is a high failure rate, and it suggests a problem in the quality of antimalarials present in distribution channels. The complexity of markets – and the number of products from different manufacturers available in these markets – seems to be one of the factors contributing to making medicines regulation more difficult and increasing the possibility of consumers obtaining access to substandard medicines on the market. |

When failure rates in imported products and locally manufactured products were compared, higher failure rates were found among locally manufactured products. This may be due to different regulatory standards for locally manufactured medicines and imported medicines. The total failure rate of samples of WHO-pre-qualified medicines collected from all six countries involved in the survey was very low – below 4 per cent, emphasizing the importance of the normative role of the WHO in medicines regulation and the importance of its pre-qualification mechanism for quality assurance of procured medicines (WHO, 2011b). |

At the international level, the problem of SFFC medicines was first addressed in 1985 at the Conference of Experts on the Rational Use of Drugs in Nairobi. The meeting recommended that the WHO, together with other international organizations and NGOs, study the feasibility of setting up a clearing house to collect data and inform governments about the nature and extent of counterfeiting. In 1988, WHO member states requested the WHO to initiate programmes for the prevention and detection of the export, import and smuggling of SFFC pharmaceutical preparations.24 The rapid spread of SFFC medicines in many national distribution channels, coupled with increasing trade and sales via the Internet, finally led to the establishment of the International Medical Products Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce (IMPACT) in 2006. IMPACT was established to raise awareness, exchange information, encourage cooperation and provide assistance on issues related to counterfeit medicines and involved international organizations, NGOs, enforcement agencies, drug regulatory authorities and pharmaceutical manufacturers. The set of draft principles and elements for national legislation against counterfeit medical products produced by IMPACT was further developed in 2007 and addressed definitional issues, responsibilities of public-sector and private-sector stakeholders, and sanctions.25

The detention of in-transit generic medicines by European custom authorities (see Section C later in this chapter) and criticism regarding the involvement of the pharmaceutical industry and other stakeholders such as INTERPOL with IMPACT triggered an intense debate. This focused on the relationship between combating substandard and SFFC medical products from a public health perspective, the enforcement of IPRs and the role that the WHO should play, or not play, including its role in IMPACT. To respond to concerns raised, the World Health Assembly (WHA) in 2010 convened a working group comprising representatives of member states. The working group was, among others, mandated to examine: the role of the WHO in ensuring the availability of good-quality, safe, efficacious and affordable medicines, and to examine its relationship with IMPACT and its role in the prevention and control of substandard and SFFC medical products. The mandate stipulated that these issues should be examined from a public health perspective, explicitly excluding trade and IP considerations.26 In May 2012, the WHA established a new voluntary member state-driven mechanism aimed at preventing and controlling substandard and SFFC medical products and associated activities from a public health perspective, excluding trade and IP considerations.27 The mechanism will regularly report to the WHA on its progress and on any recommendations arising out of its work.

(f) Other regulatory determinants that impact access

Besides the fragmentation of the supply chain and the globalization of the pharmaceutical manufacturing processes and substandard and SFFC products, many other challenges have an impact on the functioning of the regulatory systems, including:

- lack of political support coupled with regulatory authorities' inadequate human and financial resources

- lack of effective collaboration and lack of trust in other regulatory authorities' decisions, including a trend towards duplicative inspections of production facilities and assessments, which create limited added value

- focus on regulating products without effective oversight of the supply chain

- poorly developed systems for monitoring products safety after marketing authorization

- double standards whereby, for example, locally manufactured products are not required to meet the same standards as imported products (see Box 4.11).

All these challenges put regulatory systems under strain and impact the steady supply of quality medicines and other regulated medical products.

1. For a general overview of pricing policies, see OECD (2008). back to text

2. ATC system information is available from ww.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index. back to text

3. See http://whocc.goeg.at/Glossary/About. back to text

4. For a definition, see www.eunethta.eu. back to text

5. See www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/f0b1e114-e770-11e0-9da300144feab49a.html#axzz1c404Fdtv back to text

6. Sources: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/ s19111es/s19111es.pdf; http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/ documents/s19110es/s19110es.pdf; and http://apps.who. int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js19110es/. back to text

7. A revised version of 2003 is available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PROCUREMENT/Resources/ health-ev4.pdf. back to text

8. Available at www.who.int/hiv/amds/en/decisionmakersguide_ cover.pdf. back to text

9. For further information, see: www.who.int/phi/access_ medicines_feb2011/en/index.html; www.wipo.int//meetings/ en/2011/who_wipo_wto_ip_med_ge_11/; and www.wto. org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/techsymp_feb11_e/techsymp_ feb11_e.htm. back to text

10. For a review of initiatives supporting investment in local production and technology transfer in pharmaceuticals, see WHO (2011e). back to text

11. See www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/quality_ assurance/production/en/index.html. back to text

12. See Chapter II, Section B.1(g)(v). back to text

13. See http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_IVB_06.13_ eng.pdf. back to text

14. See http://apps.who.int/prequal/. back to text

15. See http://apps.who.int/prequal/query/productregistry. aspx?list=in. back to text

16. See www.who.int/medical_devices/policies/en/. back to text

17. See Directive 90/385/EEC, Directive 93/42/EEC and Directive 98/79/EC, available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/ medical-devices/regulatory-framework/index_en.htm. back to text

18. See www.who.int/medicines/services/counterfeit/en/. back to text

19. See www.who.int/medicines/services/counterfeit/WHO_ ACM_Report.pdf. back to text

20. See www.who.int/medicines/services/expertcommittees/pharmprep/43rdpharmprep/en/index.html. back to text

21. See www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs275/en/. back to text

22. Ibid. back to text

23. Ibid. back to text

24. WHA, Resolution: WHA41.16: Rational use of drugs. back to text

25. See www.who.int/impact/en/. back to text

26. WHA, Decision: WHA 63(10): Substandard/spurious/falselylabelled/falsified/counterfeit medical products. Documents of the Working Group and the new member state mechanism are available at http://apps.who.int/gb/ssffc/. back to text

27. WHA, Resolution: WHA65.19: Substandard/spurious/falselylabelled/falsified/counterfeit medical products. back to text