C. The global burden of disease and global health risks

| Key points |

|

|

|

|

|

The development of effective strategies to improve global health and react to changes in the global burden of disease (GBD) requires an understanding of the GBD and of GBD-related trends, coupled with an understanding of major health risks. These are introduced in this section.

1. Defining the need

International efforts to address public health issues need to be grounded in a clear empirical understanding of the GBD, and future efforts should be guided, as far as possible, by best estimates on the evolving disease landscape.

Measuring the global burden of disease

The WHO studies on the GBD aim to summarize overall loss of health associated with diseases and injuries. GBD measurement methods were developed in order to generate comprehensive and internally consistent estimates of mortality and morbidity by age, sex and region. The key feature of this concept is a summary measure called the disability-adjusted life year (DALY). The DALY concept was introduced as a single measure to quantify the burden of disease, injuries and risk factors (Murray and Lopez, 1996). The DALY is based on years of life lost due to premature death, and years of life lived in less than full health (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. The disability-adjusted life year

|

The DALY extends the concept of potential years of life lost due to premature death to include equivalent years of "healthy" life lost by virtue of being in states of poor health or disability (Murray and Lopez, 1996). One DALY can be thought of as one lost year of "healthy" life, and the burden of disease can be thought of as a measurement of the gap between the current health status and an ideal situation where everyone lives into old age, free of disease and disability.

|

DALYs for a disease or injury cause are calculated as the sum of the years of life lost (YLL) due to premature mortality in the population and the years lost due to disability (YLD) for incident cases of the disease or injury. YLLs are calculated from the number of deaths at each age multiplied by a global standard life expectancy of the age at which death occurs. YLD for a particular cause in a particular time period are estimated as follows:

|

YLD = number of incident cases in that period × average duration of the disease × weight factor

|

The weight factor reflects the severity of the disease on a scale from 0 (perfect health) to 1 (death).1

|

Current data on global average burden of disease

The average GBD across all regions in 2004 was 237 DALYs per 1,000 population, of which about 60 per cent were due to premature death and 40 per cent were due to nonfatal health outcomes (WHO, 2008). The contribution of premature death varied dramatically across regions, with years of life lost (YLL) rates seven times higher in Africa than in high-income countries. In contrast, the years lost due to disability (YLD) rates were less varied, with Africa having 80 per cent higher rates than high-income countries. South-East Asia and Africa together bore 54 per cent of the total GBD in 2004, although these regions account for only about 40 per cent of the world's population.

The high levels of burden of disease for the WHO regions of Africa, South-East Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean, compared with other regions, are predominantly due to Group I conditions (communicable diseases, and maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions). Injury DALY rates are also higher than they are in other regions.

Almost half of the disease burden in LMICs is currently caused by NCDs. Ischaemic heart disease and stroke are the largest sources of this burden, especially in European LMICs, where cardiovascular diseases account for more than one quarter of the total disease burden. Injuries accounted for 17 per cent of the disease burden in adults aged 15-59 years in 2004.

2. Trends and projections: major cause groups contributing to the total disease burden

The following trends and projections are the WHO estimations for the GBD from 2004 to 2030, using projection methods similar to those used in the original 1990 GBD study (Mathers and Loncar, 2006; WHO, 2008).

Global DALYs are projected to decrease by about 10 per cent in absolute numbers from 2004 to 2030. Since the population increase is projected to be 25 per cent over the same period, this represents a significant reduction in the global per capita burden. The DALY rate decreases at a faster rate than the overall death rate because of the shift in age at death to older ages associated with fewer YLLs. Even assuming that the age-specific burden for most non-fatal causes remains constant into the future, and thus that the overall burden for these conditions increases in line with the ageing of the population, there is still an overall projected decrease in the GBD per capita of 30 per cent for the period 2004 to 2030. This decrease is largely driven by projected levels of economic growth in the projection model. If economic growth is slower than recent World Bank projections, or if risk factor trends in LMICs are adverse, then the GBD will fall more slowly than projected.

The proportional contribution of the three major cause groups to the total disease burden is projected to change substantially. Group I (communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions) causes are projected to account for 20 per cent of total DALYs lost in 2030, compared with just under 40 per cent in 2004. The NCD (Group II) burden is projected to increase to 66 per cent in 2030, and to represent a greater burden of disease than Group I conditions in all income groups, including low-income countries.

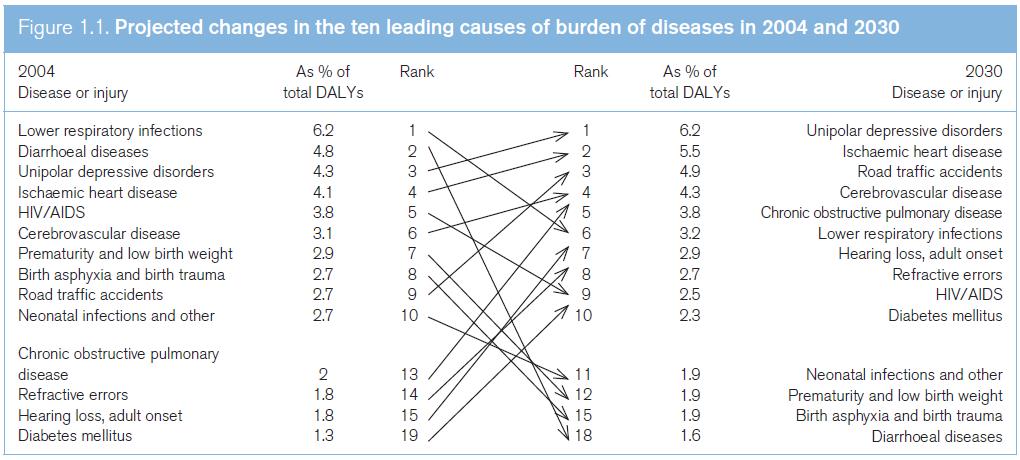

The three leading causes of DALYs in 2030 are projected to be unipolar depressive disorders, ischaemic heart disease and road traffic accidents.

Lower respiratory infections drop from leading cause in 2004 to sixth leading cause in 2030, and HIV/ AIDS drops from fifth leading cause in 2004 to ninth leading cause in 2030. Lower respiratory infections, perinatal conditions, diarrhoeal diseases and TB are all projected to decline substantially in importance. On the other hand, ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, road traffic accidents, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hearing loss and refractive errors are all projected to move up three or more places in the rankings.

Communicable diseases: trends

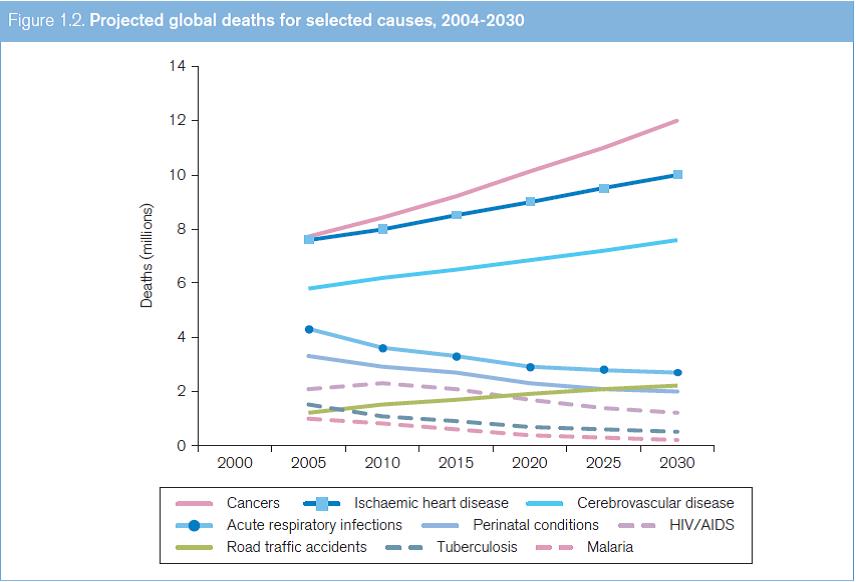

Between 2004 and 2030, large declines in mortality are projected for all of the principal communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional causes, including HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria (see Figure 1.1). HIV/AIDS deaths reached a global peak of 2.1 million in 2004, and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated 1.7 million AIDS-related deaths in 2011 (UNAIDS, 2012). Deaths are projected to decline considerably over the next 20 years under a baseline scenario that assumes that coverage with antiretroviral (ARV) treatment continues to rise at current rates.

Non-communicable diseases: trends

The ageing of populations in LMICs will result in significantly increasing total deaths due to most NCDs over the next 25 years. Global cancer deaths are projected to increase from 7.4 million in 2004 to 11.8 million in 2030, and global cardiovascular deaths from 17.1 million in 2004 to 23.4 million in 2030. Overall, non-communicable conditions are projected to account for just over three quarters of all deaths in 2030 (see Figure 1.2).

Based on these projections, people in all regions of the world will live longer and with lower levels of disability, particularly from infectious, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions. Globally, there will be slower progress if there is no sustained and additional effort to achieve progress on the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), or to address neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), tobacco smoking and other chronic disease risks, or if economic growth in low-income countries is lower than forecasted.

Trends in total deaths and major causes of death

A total of 7.1 million children died in 2010, mainly in LMICs. More than one third of these deaths were attributable to undernutrition (Liu et al., 2012). The main causes of death in children under five were deaths arising during the neonatal period (40 per cent, e.g. preterm complications, intrapartum-related complications, and neonatal sepsis or meningitis), diarrhoeal diseases (10 per cent), pneumonia (18 per cent) and malaria (7 per cent) (Liu et al., 2012; WHO, 2012c). Nearly half of these deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (49 per cent) and in Southern Asia (39 per cent) (UNICEF, 2012).

During 2008, an estimated 57 million people died (WHO, 2011a). Cardiovascular diseases kill more people each year than any other disease. In 2008, 7.3 million people died of ischaemic heart disease and 6.2 million from stroke or another form of cerebrovascular disease (see Table 1.1). Tobacco use is a major cause of many fatal diseases, including cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. In total, tobacco use is responsible for the deaths of almost one in ten adults worldwide.

| Table 1.1. The ten leading causes of death globally, 2008

|

||

World

|

Deaths in millions

|

Percentage of deaths

|

| Ischaemic heart disease

|

7.25 | 12.8 |

Stroke and other cerebrovascular disease

|

6.15 |

10.8 |

| Lower respiratory infections

|

3.46 | 6.1 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

|

3.28 |

5.8 |

| Diarrhoeal diseases

|

2.46 | 4.3 |

HIV/AIDS

|

1.78 |

3.1 |

| Trachea, bronchus, lung cancers

|

1.39 | 2.4 |

TB

|

1.34 |

2.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus

|

1.26 | 2.2 |

Road traffic accidents

|

1.21 |

2.1 |

Source: WHO, Fact Sheet No. 310, 2011.

There are some key differences between rich and poor countries with respect to causes of death:

- In high-income countries, more than two thirds of all people live beyond the age of 70 and predominantly die of chronic diseases: cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancers, diabetes or dementia. Lower respiratory infection remains the only leading infectious cause of death.

- In middle-income countries, nearly half of all people live to the age of 70, and chronic diseases are the major killers, just as they are in high-income countries. Unlike in high-income countries, however, TB, HIV/ AIDS and road traffic accidents also are leading causes of death.

- In low-income countries, fewer than one in five of all people reach the age of 70, and more than a third of all deaths are among children aged under 15 years. People predominantly die of infectious diseases: lower respiratory infections, diarrhoeal diseases, HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. Complications of pregnancy and childbirth together continue to be leading causes of death, claiming the lives of both infants and mothers.

3. Global health risks

The WHO has also attributed mortality and burden of disease to selected major risks. In this context, the WHO defines "health risk" as "a factor that raises the probability of adverse health outcomes" (WHO, 2009). The leading global risks for mortality in the world are high blood pressure (responsible for 13 per cent of deaths globally), tobacco use (9 per cent), high blood glucose (6 per cent), physical inactivity (6 per cent), and overweight and obesity (5 per cent) (WHO, 2009). These risks are responsible for raising the risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes and cancers. They affect countries across all income groups: high, middle and low.

The leading global risks for burden of disease as measured in DALYs are underweight (6 per cent of global DALYs) and unsafe sex (5 per cent), followed by alcohol use (5 per cent) and unsafe water, sanitation and hygiene (4 per cent). Three of these risks particularly affect populations in low-income countries, especially in the regions of South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The fourth risk – alcohol use – shows a unique geographic and sex pattern, with its burden highest for men in Africa, in middle-income countries in the Americas and in some high-income countries.

The WHO identified the following risk factors:

- Five leading risk factors (childhood underweight, unsafe sex, alcohol use, unsafe water and sanitation, and high blood pressure) that are responsible for one quarter of all deaths in the world and one fifth of all DALYs. Reducing exposure to these risk factors would increase global life expectancy by almost five years.

- Eight risk factors (alcohol use, tobacco use, high blood pressure, high body mass index, high cholesterol, high blood glucose, low fruit and vegetable intake, and physical inactivity) account for 61 per cent of cardiovascular deaths. Combined, these same risk factors account for over three quarters of ischaemic heart disease – the leading cause of death worldwide. Although these major risk factors are usually associated with high-income countries, over 84 per cent of the total GBD they cause occurs in LMICs. Reducing exposure to these eight risk factors would increase global life expectancy by almost five years.

- A number of environmental and behavioural risks, together with infectious causes – such as blood and liver flukes, human papillomavirus, hepatitis B and C virus, herpesvirus and Helicobacter pylori – are responsible for 45 per cent of cancer deaths worldwide (WHO, 2009). For specific cancers, the proportion is higher: for example, tobacco smoking alone causes 71 per cent of lung cancer deaths worldwide. Tobacco accounted for 18 per cent of deaths in high-income countries.

Health risks are in transition: populations are ageing due to successes against infectious diseases. At the same time, patterns of physical activity as well as food, alcohol and tobacco consumption are changing. LMICs now face a double burden of increasing chronic, non-communicable conditions, as well as the communicable diseases which traditionally affect the poor. Understanding the role of these risk factors is important for developing clear and effective strategies for improving global health (WHO, 2009).

The weights used for the GBD 2004 are listed in Annex Table A6 of Mathers et al. (2006). back to text