A. Access to medical technologies: the context

Key points

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This chapter offers an overview of the main determinants of access related to health systems, intellectual property (IP) and trade policy. Many other very important socio-economic factors determine access to medical technologies – factors such as health financing, the importance of a qualified health care workforce, poverty and cultural issues – and lack of access is rarely due entirely to a single determinant but these are not addressed in this study, as they are not part of the interface between health, IP and trade.

Multiple factors must interact in order to create sustainable access to medical technologies. Pneumonia, the single largest cause of death in children worldwide, provides an illustration of the complexity of the access problem. Every year, this disease kills nearly 1.3 million children under the age of five years, accounting for 18 per cent of all deaths of children of this age worldwide – more than AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined (UNICEF, 2012; WHO, 2012c). Children can be protected from pneumonia – it can be prevented by simple interventions, and it can be treated with low-cost, low-tech medication and care.1 This example of basic and inexpensive medicines that are still inaccessible clearly indicates that barriers to access are more complex than affordability alone.

Lack of access is generally understood to mean the absence of available treatment options for the patient. Appropriate treatment has to be physically available and needs to be affordable for the patient.

In high-income countries a high percentage of expenditures on medical technologies is publicly financed or reimbursedby health insurance schemes, in LMICs, most health care expenditure is paid by patients out of their own pockets.

Medical technologies are complex products that can only be effective in conjunction with expert advice and other health services. The issue of access to medicines is one aspect of a broader problem of access to health care. Delivering access requires a functioning national health care system. Providing needed medications to patients is just one component of that system.

The WHO has defined "access" to medicines as the equitable availability and affordability of essential medicines during the process of medicine acquisition (WHO, 2003b; 2004c). To describe the required conditions for ensuring access to medicines, the WHO has developed an access framework for essential medicines.

1. The WHO access framework for essential medicines

The WHO access framework for essential medicines consists of four determinants that need to be fulfilled simultaneously in order to provide access to medicines (WHO, 2004c):

- rational selection and use of medicines

- affordable prices

- sustainable financing

- reliable health and supply systems.

Improved access to medicines will only provide public health benefits if it also involves improved access to quality products. The necessary stringent quality assurance and regulation of quality of health products is the responsibility of manufacturers, suppliers and national regulatory authorities. The WHO framework on access assumes quality and regulation of medicines as an integral part of access to medicines.

Other frameworks for access to medicines have been formulated over time. In addition to the WHO framework, health policy experts have proposed a framework revolving around the so-called "5As" of availability, accessibility, affordability, adequacy and acceptability (Obrist et al., 2007).2 The most recently developed framework pays more attention to the international aspects of partnerships for access to medicines (Frost and Reich, 2010).

The following sections briefly summarize the four determinants of access outlined in the WHO framework for access to essential medicines.

(a) Rational selection and use of medicines

Rational selection of medicines requires a country to decide, according to well-defined criteria, which medicines are most important in order to address the national burden of disease. Through its work on the WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines (EML), the WHO has provided guidance to countries on the development of their own national essential medicine lists (see Box 4.1).

A list of essential medicines can help countries prioritize the purchasing and distribution of medicines, thereby reducing costs to the health system by focusing on the essential products needed. The addition of a medicine to the WHO EML directly encourages individual countries to add the drug to their national EML and to internal drug registries. Some countries restrict drug importations to medicines based on their national EML. Similarly, several foundations and major charities base their medicine supply on the WHO EML. In 2003, 156 countries had developed national essential medicines lists and in 2009 WHO reported that 79 per cent countries had updated their national EMLs in the last five years.3

Equally important as rational selection of medicines is their rational use. Irrational use – the inappropriate, improper, incorrect use of medicines – is a major problem worldwide. Irrational use can cause harm through adverse reactions and increase antimicrobial resistance (Holloway and van Dijk, 2011) and can waste scarce resources. One example is the use of antibiotics in Europe where some countries use three times as many antibiotics per capita as do other countries with similar disease profiles (Holloway and van Dijk, 2011). Examples of irrational use include:

- the use of too many medicines per patient (poly-pharmacy)

- the use of unnecessary medicines

- the use of the incorrect medicine for a condition

- the failure to prescribe a necessary medicine.

In addition, problems with irrational use arise over issues of formulation (such as oral or paediatric formulations), inappropriate self-medication, and non-adherence to dosing regimens by both prescribers and patients. Worldwide patient adherence to treatment has been estimated to be about 50 per cent (Holloway and van Dijk, 2011), and in many cases where medicines are dispensed, the instructions given to the patient and the labelling of the dispensed medicines are inadequate.

The development of evidence-based clinical guidelines is an important tool to promote rational selection and use of medicines. Such development, however, is challenging, especially with regard to NCDs. The pharmaceutical industry is heavily engaged in this disease area because of the long-term market potential of treatments for chronic diseases which requires a careful analysis and management of potential conflicts of interest between the industry, patient organizations, professional associations, health insurance and public-sector organizations.4

Box 4.1. The WHO Model List of Essential Medicines |

Essential medicines are "those that satisfy the priority health care needs of the population ... . Essential medicines are intended to be available within the context of functioning health systems at all times in adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms, with assured quality and adequate information, and at a price the individual and the community can afford. The implementation of the concept of essential medicines is intended to be flexible and adaptable to many different situations; exactly which medicines are regarded as essential remains a national responsibility" (WHO, 2002a). |

The first EML was published in 1977. Selection criteria were developed relating to safety, quality, efficacy and total cost (Mirza, 2008; Greene, 2010). The 17th EML contains 445 medicines and 358 molecules excluding duplicates (van den Ham et al., 2011), and includes treatment options for malaria, HIV/AIDS, TB, reproductive health and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes, based on the best available evidence (WHO, 2011d). In 2007, the first EML for children was developed and published (WHO, 2011f). |

The EML provides guidance about the medicines recommended to treat common health problems. It typically includes all of the medicines recommended in standard treatment guidelines, as well as other medicines needed to address most of the clinical problems at a given level of care. |

The EML lists medicines by their international nonproprietary name (INN), also known as the generic name, without specifying a manufacturer. The list is updated every two years by the WHO Expert Committee for the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, using a transparent, evidence-based process. |

Before 2002, expensive medicines were often not included on the EML as the selection criteria emphasized the need for low-priced medicines. The main criterion for selection today is effectiveness. In the evaluation process, information on comparative cost and cost-effectiveness must be presented, for example, as cost per case prevented or cost per quality-adjusted life year gained. Cost still can be relevant for the selection within a therapeutic class to identify the best value for money if efficacy is comparable (van den Ham et al., 2011). If an expensive but cost-effective medicine is placed on the EML, this implies that it must become available and affordable. First-line antiretrovirals (ARVs) were the first notable example of this new approach and they were added to the EML in 2002. At that time, they cost over US$ 10,000 per patient per year. Since then, prices have decreased dramatically. |

With the exception of a number of mainly HIV/AIDS medicines, the vast majority of medicines on the EML are off patent and generic versions are widely available, including medicines for the main NCDs (Attaran, 2004; Mackey and Liang, 2012). |

(b) Affordable prices

Another important determinant for access to medicines is price and affordability. Affordability depends on a number of factors, including the question of reimbursement, or whether the expense is one-time or recurring. To assess affordability, the price of the medicines must first be established and then compared with available resources.

Prices of medicines are a critical determinant of access to medicines, especially in countries where the public health sector is weak and poor people have to purchase their treatment on the private market and pay for it out of their meagre resources. In some developing countries, up to 80 per cent to 90 per cent of medicines are purchased out-of-pocket as opposed to being paid for by national health insurance schemes or private insurance schemes (WHO, 2004c). Poor patients are willing to pay more for medicines than they would for other consumer goods, but, nonetheless, may face unaffordable prices. For this important reason, many governments regulate medicine prices (see later in this chapter).

Data on the availability of medicines and consumer prices are poor in most developing countries, but surveys of medicines prices and availability have been conducted in the past years by HAI and the WHO (WHO/HAI, 2008). Prices are typically reported as median prices in the local currency and also as median price ratios (MPRs), which compare local prices with a set of international reference prices (IRPs) reported by Management Sciences for Health.5 MPRs allow for simple expression of the difference between median local medicine prices and the IRP. An IRP represents actual procurement prices for medicines offered to LMICs by non-profit suppliers, and usually does not include freight costs (Cameron et al., 2009). An MPR of 2, for example, means that the local medicine price is twice the IRP, whereas an MPR of less than 1 means that the local price is less than the IRP.

"Affordability" is calculated by the WHO as the number of days' wages of the lowest-paid, unskilled government worker required to purchase selected courses of treatment for common acute and chronic conditions (WHO/HAI, 2008).

Total health care expenditures can be considered "catastrophic" if they exceed 10 per cent of a household's total resources or 40 per cent of non-food expenditure (Wagner et al., 2011).

Another measure of affordability requires assessing the proportion of the population that would be pushed below the international poverty lines of US$ 1.25 or US$ 2 a day because medicines or medical care were purchased. One study of 16 LMICs finds that substantial proportions of these countries' populations would be pushed below the poverty line as a result of purchasing four common medicines, and an even greater proportion would be in this situation if they used originator products (Niëns et al., 2010). For further discussion of generic availability and pricing, see Section B.1 of this chapter.

IP protection plays a role in determining the affordability of medical technologies. Generic medicines are, on average, cheaper than originator products, in part due to price competition between producers. The WHO analysed availability and affordability of essential medicines in the public and private sectors in 46 LMICs between 2001 and 2009. "Availability" was defined as the percentage of outlets where an individual medicine product could be physically located on the day of the survey (WHO/HAI, 2008). These surveys of selected generic medicines indicate that the global average median availability of such medicines in the public sector is less than 42 per cent (WHO, 2012c). Generally, availability of generics is higher in the private sector – almost 72 per cent in the same studies – although in many parts of the world, the private sector prefers to stock originator products. Even for generic products, prices in the private sector tend to be higher. Prices for even the lowest-priced generic products in the private sector, adjusted for purchasing power parity, were at least nine to 25 times the IRP in most WHO regions. For originator products, private-sector prices were at least 20 times higher than the IRP in all WHO regions (Cameron et al., 2009). For unadjusted country data on generic prices and availability, see WHO (2012c) (see also data in UN, 2011b; 2012).

It is estimated that costs to patients could be 60 per cent lower in the private sector if generics were stocked preferentially over originator products (Cameron and Laing, 2010). However, the poorest populations may not be able to afford even the lowest-priced generic products, especially when they are only available through the higher-priced private system (Niëns et al., 2010). It is estimated that each year up to 10 per cent of the population in the 89 countries for which data are available suffers financial catastrophe and impoverishment associated with direct out-of-pocket payments for health (WHO, 2012c). Ensuring availability of medicines at little or no cost through the public health system is thus critical for universal access and a primary responsibility of governments.

(c) Sustainable financing

Sustainable financing of health systems is a prerequisite for a steady supply of medicines and other medical technologies. Per capita expenditure on health care tends to be low in low-income countries, although a large proportion usually goes to medicine purchases – between 20 per cent and 60 per cent of the recurrent health budget.6 The Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (CMH) recommended that developing countries raise domestic budgetary spending on health to 2 per cent of their gross national product by 2015, with the goal of achieving universal access to essential health services. The CMH also recommended that donor countries commit significant financing and investment to health research and development (R&D) by coordinating with and drawing additional resources from international and intergovernmental organizations (WHO, 2001a). Policy-makers should have as objectives, among others: to increase public funding for health, including for essential medicines; to reduce out-of-pocket spending by patients, especially by the poor; and to expand health insurance coverage (WHO, 2004c).

In 2009, in 36 out of 89 countries for which data are available out-of-pocket expenditures for health accounted for more than 50 per cent of total health spending (WHO, 2012c).

Since 2001, the world has seen a significant increase in international funding for essential medicines in certain disease areas, vaccines and other medical products such as antimalarial bed nets, for distribution to poorer countries, including through mechanisms such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), UNITAID, the GAVI Alliance, the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) and other international initiatives. This has vastly improved access to these products in many countries. Such donor assistance and development loans can help fund health-sector financing, but it must also be provided on sustainable terms.

A commitment of the government to adequately and sustainably fund the national health system is the key condition for reaching universal (health) coverage, meaning that all people in a country have access to adequate health services.

(d) Reliable health and supply systems

Another precondition for providing access to medicines is a reliable, functioning health system that is able to supply patients with needed medical technologies of adequate quality in a timely manner. These systems include the ability to forecast needs, as well as to procure, store, transport and inventory medicines and medical devices and distribute them appropriately. Supply systems remain weak and fragmented in many developing countries as can be seen from Figure 4.1, which captures Tanzania's complex pharmaceutical supply chain. The first row of boxes in the map corresponds to categories of products designated by a specific colour. The next row represent various partners supporting the different categories of products identified by a specific colour under the four main groups of donors (government, bilateral, multilateral and NGO or private). The third row of boxes stands for the agents, which procure products on behalf of financing partners. The last three but one row of boxes represent the various levels of warehousing before the products reach the patient.

The mapped medical products are funded by 22 donors, procured in various ways through 19 actors, warehoused in two stages involving 14 different entities, and finally reach patients through six divergent points of distribution. The map illustrates the challenges of managing and coordinating a supply chain flowing through five levels adding new actors at each stage, and shows that some products such as ARVs are supported by more donors than others, for example, contraceptives and TB have only two donors each (Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, 2008). Similar fragmentations of the supply chain can be found in many other countries.

Without improvement, access to medicines and other needed medical technologies will remain a formidable challenge. Adequate regulatory capacity is also required to ensure access to safe and effective medicines for both imported and domestically manufactured medicines.

Another key component of a reliable health system necessary to ensure access to medicines is a strong health workforce. Current data on health workforce can be found in WHO global atlas of the health workforce.7

For policy-makers the key issues are: to integrate medicines more directly into health-sector development; to create more efficient mixes of public-private-NGO approaches in medicines supply; to have regulatory control systems that provide assured quality medicines; to explore creative purchasing schemes; and to include traditional medicines in the provision of health care (WHO, 2004c). More research is needed in this area. The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research adopts a health systems perspective on access to medicines (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research: access to medicines

|

Since 2010, the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research has been leading the Access to Medicines Policy Research project, which adopts a health systems perspective on access to medicines. It acknowledges that vertical, fragmented approaches, usually focusing on medicines supply and unrelated to the wider issue of access to health services and interventions, may not be effective in addressing the need for populations' access to medicines. |

This project led to a call for proposals formulated around the following three questions: |

|

2. Access to medicines in specific areas

While access to medicines remains a problem in all disease areas, this section focuses on a number of particular areas – HIV/AIDS, NCDs, paediatric medicines and vaccines – because of their specificity and importance.

(a) HIV/AIDS

Access to antiretroviral (ARV) therapy in LMICs has grown dramatically in recent years, with coverage increasing from only 400,000 people living with HIV in 2003 to more than 8 million by the end of 2011. AIDS-related deaths dropped by 24 per cent globally over the period 2005 to 2011 alone (UNAIDS, 2012).

The main drivers of this increased coverage are donor commitment and decreasing prices of ARVs. Substantial price reductions for commonly used first-line ARVs have been achieved since 2000. The annual cost of first-line regimens in low-income countries decreased from over US$ 692 per person in 2000 to a weighted median price of US$ 121 per person for the ten most widely used first-line regimens in 2010, representing a reduction of more than 98 per cent (WHO/UNAIDS/ UNICEF, 2011). Prices for second-line regimens are much higher, ranging between US$ 554 for the most common regimen in low-income countries and US$ 692 in middle-income countries.9 These reductions are due to many factors, including:

- increased funding for ARV therapy and emergence of a generic ARV market creating economies of scale

- political will at national and international levels to provide treatment due to pressure from HIV/AIDS activists

- creation and use of the WHO standard treatment guidelines .

- use of compulsory licences and government use

- the rejection of patent applications in key producing countries, thus enabling generic companies to compete

- price decrease of originator products and voluntary licence agreements and non-assert declarations .

- price negotiations, including by bulk purchasers

- enhanced price transparency through ARV price publications and databases.10

The need for affordable ARVs further increased following two developments:

- The adoption of updated WHO HIV treatment guidelines, which recommended starting treatment earlier in the disease course in order to reduce HIV-related mortality and prevent opportunistic infections such as TB.

- Strengthened evidence on the HIV prevention benefits of ARV therapy, resulting in the adoption of new WHO guidelines on the use of ARVs for HIV prevention in HIV discordant couples. Consideration should also be given to the use of ARVs for HIV prevention in other populations (WHO, 2012b).

Lower prices for ARVs are essential if governments and donor agencies are to meet the target of having 15 million people with HIV receiving ARV treatment by 2015, as set out in the 2011 UN Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS. They are also essential if governments and donor agencies are to meet their commitments to keep patients on lifelong ARV therapy (UN, 2011a).

The impact of patents on access to medicines has often been illustrated using the example of HIV/AIDS. Access to ARVs has presented a unique challenge because the earliest effective treatments became available only in the late 1980s. Thus, while today older HIV/AIDS treatments are available from generic sources, more recently developed ARVs are still patent protected in many countries.11

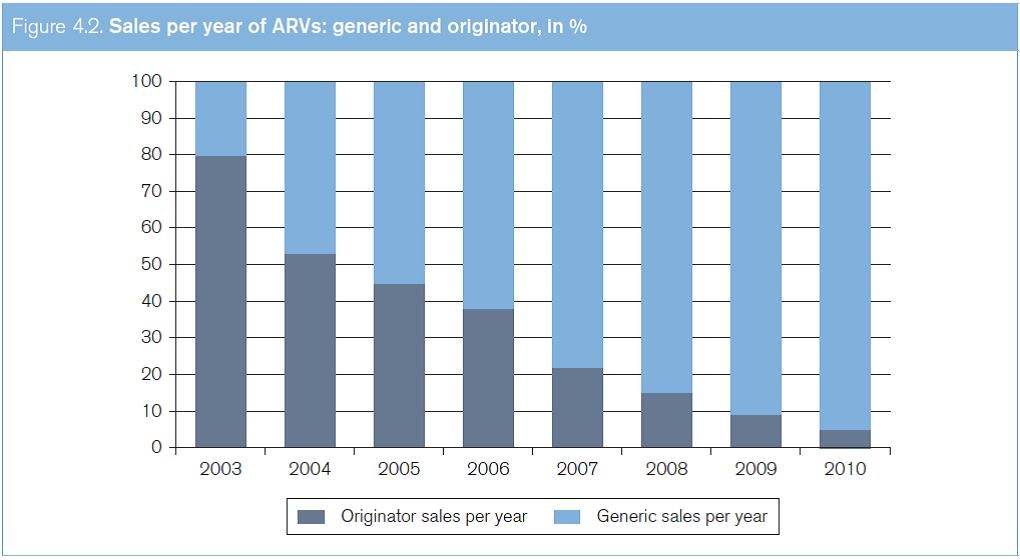

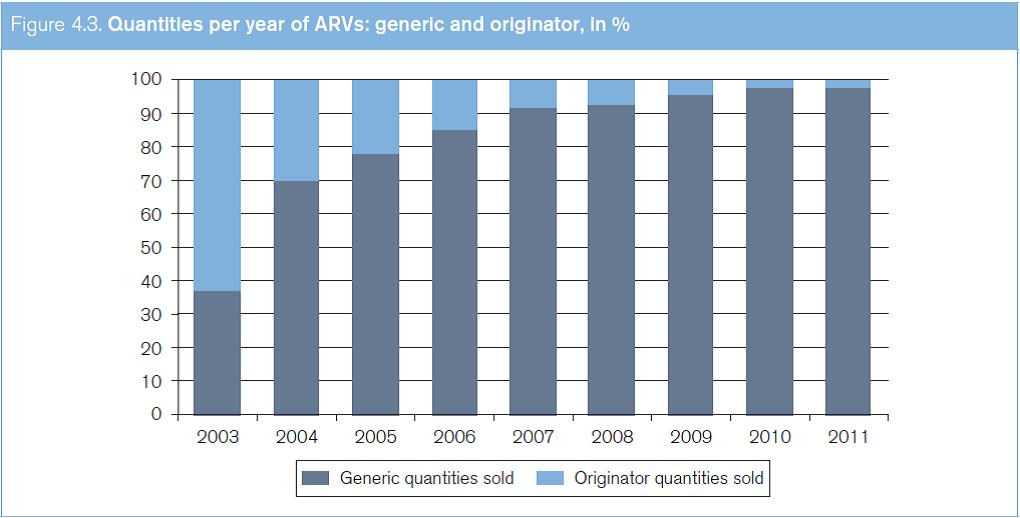

Figure 4.2 shows the increases in generic ARVs in terms of sales between 2003 and 2011. The data are sourced from the WHO Global Price Reporting Mechanism for HIV, TB and malaria. This reporting mechanism is a database which records international transactions of HIV, TB and malaria commodities purchased by national programmes in LMICs. Figure 4.3 shows the increases in the quantities of generic ARVs sold between 2003 and 2011.

Source: Global Price Reporting Mechanism for HIV, tuberculosis and malaria at www.who.int/hiv/amds/gprm/en/ and Transaction Prices for Antiretroviral Medicines and HIV Diagnostics from 2008 to July 2011 at www.who.int/hiv/pub/amds/gprm_report_oct11/ en/index.html.

Source: Global Price Reporting Mechanism for HIV, tuberculosis and malaria at www.who.int/hiv/amds/gprm/en/ and Transaction Prices for Antiretroviral Medicines and HIV Diagnostics from 2008 to July 2011 at www.who.int/hiv/pub/amds/gprm_report_oct11/ en/index.html.

Indian companies provide most of the generic ARVs in the world, far exceeding those produced by non-Indian generic companies or originator companies. Since 2006, generic ARVs from India have accounted for more than 80 per cent of the donor-funded, developing-country market (Waning et al., 2010). India's important role in the generic ARV market is due to a number of factors, including the fact that a pharmaceutical patent regime did not exist in India until 2005, thus allowing Indian-based companies to produce generic versions of ARVs which were still under patent in other jurisdictions. As a result of the introduction of the product patent regime in India in 2005, pharmaceutical product patents will be granted in India and, consequently, generic versions of new treatments will only be available after patent expiration. Already, certain ARVs newly recommended by the WHO are much more expensive than older regimens, and are also patented more widely, including in India and other major generics-producing countries.12

The 2011 Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS commits UN member states to remove, where feasible, obstacles limiting the capacity of LMICs to provide affordable and effective HIV prevention and treatment by 2015, including reducing costs associated with lifelong chronic care through the use of the flexibilities contained in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement)13 and the promotion of generic competition. The Declaration also encourages the voluntary use of other mechanisms to promote access – for example, tiered pricing, open-source sharing of patents and patent pools, including through entities such as the Medicines Patent Pool – in order to help reduce treatment costs and encourage development of new HIV treatment formulations (UN, 2011a).

(b) Non-communicable diseases

Until recently, the emphasis on "access" to medicines has primarily been directed towards infectious, communicable diseases. Now, however, demographic and epidemiological transitions demand that additional focus should be placed on access to the medical technologies that are needed to treat NCDs. According to the WHO Global Status Report on Non-Communicable Diseases, 36 million of the 57 million (63.2 per cent) global deaths in 2008 were due to NCDs, principally cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancers and chronic respiratory diseases (WHO, 2010b). Almost 80 per cent of these deaths occur in LMICs and 85 per cent of the world's population lives in LMICs.14 NCDs thus are the most common causes of death in most countries, with the exception of Africa.15 While prevention of NCDs is a key objective, access to essential medicines to treat cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) including asthma, many cancers (including palliative pain treatment) and depression must be ensured. However, providing treatment for chronic diseases puts an enormous and continuous financial strain on household budgets, often necessitating catastrophic health expenditures and thus pushing families below the poverty line (Niëns et al., 2010).

In considering how to meet the challenge of NCDs, certain parallels can be drawn with HIV/AIDS, which is now generally managed as a chronic disease. There is, nevertheless, a major difference with regard to the role of IP: while HIV/AIDS treatment has been developed relatively recently, and thus is still more widely patented, virtually all of the treatments for NCDs that are on the WHO EML are now off patent and the majority of essential medicines to treat NCDs are low-cost medicines (NCD Alliance, 2011; Mackey and Liang, 2012). Patents play a role with regard to prices of more recent medicines. It is, however, important to carefully assess the public health benefits of new treatments. Many of the higher-priced treatments for NCDs are not superior, or are only marginally better than older, existing treatments.16

Currently, major gaps in access to both originator and generic medicines for chronic diseases persist (Mendis et al., 2007). A study comparing the mean availability of 30 medicines for chronic and acute conditions in 40 developing countries found that availability of medicines for chronic diseases was lower than for acute conditions in both public and private-sector facilities (Cameron et al., 2011). Low public-sector availability of essential medicines is often caused by a lack of public resources or under-budgeting, inaccurate demand forecasting, and inefficient procurement and distribution.17

New strategies for the provision of affordable quality medicines for chronic disease will require a level of effort not unlike the efforts that have been made for treating HIV/AIDS patients. The 2011 UN Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases18 commits UN member states to improve accessibility to safe, affordable, effective and quality medicines and technologies to diagnose and to treat NCDs. The Global NCD Action Plan 2013-2020, which is under development, will seek to facilitate the implementation of this commitment through the strengthening of health systems and the monitoring of progress to achieve the global voluntary targets which include access to basic technologies and essential NCD medicines.

(c) Paediatric medicines

In 2006, a joint report produced by the WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) highlighted the need for the creation of an essential medicines list for children (WHO/UNICEF, 2006). The first WHO Model List of Essential Medicines List for Children was published in October 2007 (WHO, 2011f).19

Availability of paediatric medicines is low in many LMICs. One study found that in 14 African countries a given paediatric formulation was available in between 28 per cent and 48 per cent of primary health care clinics. Availability at retail or private pharmacies tended to be higher, ranging between 38 per cent and 63 per cent (Robertson et al., 2009).

For many medicines, paediatric formulations have not yet been developed.20 The WHO has identified products for the prevention and treatment of TB – particularly in HIV-infected children – and products for new born care as among the most urgent priorities pharmaceutical research for children's medicines.21

There are a number of reasons for the lack of research in paediatric medicines. Markets for paediatric medicines tend to be more fragmented than those for adult formulations. The reasons for such fragmentation include the fact that, of necessity, doses of medicines for children are determined by body weight. In addition, paediatric medicines must be available in flexible dosage forms, they must be pleasant tasting and they must be easy for children to swallow.22 Furthermore, it is more expensive to conduct clinical trials in children.23 In order to provide more incentives to pharmaceutical companies to develop new paediatric formulations, some geographical regions, including Europe and the United States, have introduced paediatric patent term extensions or market exclusivity periods that provide for an additional period of market exclusivity for the product if a paediatric formulation is developed.

Because paediatric formulations are a niche and potentially economically unattractive market, improving access requires extensive collaboration between the public and private sectors. One international effort to improve access to paediatric medicines is UNITAID's work in the area of paediatric ARVs. In cooperation with the Clinton Foundation, UNITAID has provided predictable funding for the large-scale purchase of paediatric ARVs, creating incentives for producers of paediatric ARVs.24 These efforts have resulted in an increase of the number of suppliers and a decrease in the price of quality AIDS medicines for children (UNITAID, 2009; UNITAID, 2011).

(d) Vaccines

National immunization programmes are a highly effective public health tool for the prevention of illness and the spread of infectious diseases, and they are almost always cost-effective in terms of public health outcomes (WHO, 2011c).

The WHO, UNICEF and the World Bank estimate that the cost of immunizing a child in developing countries is about US$ 18 per live birth (WHO/UNICEF/ World Bank, 2009). Protecting more children through vaccination with existing vaccines and introducing new vaccines in immunization programmes will represent an important contribution towards reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), including Goal 4, "Target 4A: Reduce by two thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate". The inclusion of new vaccines in immunization programmes, including pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, will help countries to reach the MDGs, but will lead to an increase in costs to about US$ 30 per live birth (WHO/UNICEF/World Bank, 2009). The arrival of new manufacturers on the market in the next three to seven years could contribute to lower prices in the future.

The degree of access to vaccines varies according to disease area. Global immunization coverage for children is almost 80 per cent for the six vaccines covered in the Expanded Programme on Immunization (i.e. vaccines against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, measles and TB) (WHO, 2011c). The work of the GAVI Alliance has contributed significantly to the immunization of children in developing countries (see Box 4.3). If countries raised the global vaccine coverage against childhood diseases to 90 per cent by 2015, an additional two million childhood deaths per year could be averted. This could significantly impact MDG 4 (WHO/UNICEF/World Bank, 2009). The main challenge in this regard is not the price of the vaccines, but the difficulty in reaching populations in remote regions, weak health and logistical support systems, a lack of understanding about the importance of vaccines and, in certain cases, misconceptions about the safety of vaccines, especially in poorer populations (WHO/ UNICEF/World Bank, 2009).

Box 4.3. GAVI Alliance |

The GAVI Alliance (formerly known as the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization), a public private partnership, funds new and under-used vaccines for children living in the 70 poorest countries in the world. By the end of 2011, the GAVI Alliance had contributed to the immunization of about 326 million children worldwide, averting more than five and a half million deaths. Since its launch in 2000, the GAVI Alliance has committed US$ 7.2 billion, 80 per cent of which has been committed to the purchase of vaccines. It also provides support to strengthen national health systems and civil society organizations to improve vaccine delivery to developing countries (57 eligible countries as of 2011 that have a per capita gross national income equal to or less than US$ 1,520) for GAVI funding.25 |

In terms of access to newer vaccines (such as those against human papillomavirus (HPV), rotavirus and pneumococcal disease), huge inequalities exist between developed and developing countries. Two of the greatest sources of child mortality in developing countries (pneumonia and diarrhoeal diseases) are often preventable with the newer vaccines, but these vaccines are not generally available in developing countries (WHO, 2011c). By 2008, only 31 countries (primarily in the developed world) had introduced the pneumococcal vaccine (WHO/UNICEF/World Bank, 2009). Currently, the vaccines remain relatively expensive due to the limited number of producers (Oxfam/MSF, 2010). Several Indian, Brazilian and Chinese manufacturers have plans to produce HPV, pneumoccocal and rotavirus vaccines in the near future, and this may, in turn, result in lower prices and improved access.

While in the area of medicines, new and innovative products are often protected by product patents, in the area of vaccines, a lack of technical skills and expertise (know-how) has frequently been the barrier to increasing the number of producers. Setting up a vaccine manufacturing plant requires a highly skilled workforce and broad technical experience and knowledge which may be specific to only one particular vaccine. For example, the reason for the limited number of manufacturers of pandemic influenza vaccines (an issue which posed challenges during 2009/2010 H1N1 pandemic influenza) was the lack of the necessary know-how and the limited market for seasonal influenza vaccines in developing countries.26

3. Access to medical devices

Medical devices play a crucial role in the prevention, diagnosis, treatment and management of medical conditions. Obtaining the benefits of medical devices is dependent to a large extent on a functioning health system, including necessary human resources capable of handling more complicated devices. It is also dependent on financing systems for reimbursement and the available infrastructure. For example, an infusion pump used to infuse medication or nutrients into a patient's circulatory system alone will not solve the patient's problem; it will only benefit the patient if the health system also provides the needed medication or fluid nutrition as well as complementary services to screen, diagnose, treat and rehabilitate. Thus, there is a need for integrated health care delivery models in which medical devices are one part of the overall health system.

The maturation of the concept of "essential" medicines has led to discussions about the application of the framework to other medical technologies. These discussions regarding "essential" medical devices are still at an early stage. While it is clear that some devices are indispensable in order to provide adequate treatment, no consensus has been reached on the issue of what could be considered essential medical devices. This is because the effectiveness of such devices might be dependent on the level of care, the infrastructure and the epidemiology in a specific region.

The issue of access to medical devices has barely been researched. It is necessary to carry out operational research to assess the current situation, develop reference documents, guidelines, standards and legislation (WHO, 2010a). There is a need to determine whether the current medical devices on the global market adequately meet the needs of health care providers and patients throughout the world and, if not, to propose remedial action. In 2010, the WHO Priority Medical Devices report identified gaps in the availability of medical devices and highlighted obstacles that hinder the full use of medical devices as public health tools (WHO, 2010a). Based on these findings, the WHO developed an approach to identify the most important health problems on a global level – a process that involved using the WHO global burden of disease framework and disease risk factor estimates. Clinical guidelines were used to identify how best to manage the most important health problems, with a particular emphasis on devices. Unfortunately, however, the clinical guidelines do not specify which devices are required to perform certain procedures and thus their implementation becomes quite complicated if the decision makers do not know which devices to select, procure and use. The third and final step linked the first two steps together to produce a list of key medical devices in the form of an availability matrix needed for the management of the identified high-burden conditions, at a given health care level and in a given context (WHO, 2010a). Overall, the need to have appropriate, affordable, accessible and safe medical devices remains a major challenge in many parts of the world, both for health systems and for the medical device industry.

1. See www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs331/en/index. html. back to text

2. Availability represents the degree of fit between existing services and clients’ needs (e.g. the correct medicines and therapies available for the current disease burden; personnel able to diagnose and treat diseases). Accessibility represents how well the geographical location of health service delivery matches the location of patients and whether patients can physically access these services (e.g. the distances and transport to health services). Affordability represents how prices for health services match clients’ ability to pay (e.g. patients can pay fees out of pocket but without selling important assets; patients can pay through health insurance; services are free). Adequacy represents how the health services organization and logistics meets clients’ expectations and needs (e.g. the hours of service match the schedules of clients and they are acceptable also to health personnel). Acceptability represents how well the match is between the provider and clients (e.g. how well the provider communicates with the client during medical consultations; how satisfied the clients are with the quality of care). back to text

3. WHO Medicines Strategies 2004-07 and 2008-13 are available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_ EDM_2004.5.pdf and www.who.int/medicines/publications/ medstrategy08_13/en/index.html. back to text

4. See www.who.int/medicines/areas/policy/access_noncommunicable/NCDbriefingdocument.pdf. back to text

5. See http://erc.msh.org/dmpguide/pdf/ DrugPriceGuide_2010_en.pdf. back to text

6. See http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/ s18767en/s18767en.pdf. back to text

7. See www.who.int/globalatlas/autologin/hrh_login.asp. back to text

8.See www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/projects/medicines/en/ index.html. back to text

9. See http://whqlibdoc.who.int/ publications/2011/9789241502986_eng.pdf. back to text

10. For example, see the WHO Global price reporting mechanism, at www.who.int/hiv/amds/gprm/en/. See also http://utw.msfaccess.org/. back to text

11. See http://utw.msfaccess.org/. back to text

12. For more details on this situation, see http://utw.msfaccess.org/. back to text

13. See Chapter II, Section B.1(g). back to text

14. See www.worldbank.org/depweb/english/modules/social/ pgr/. back to text

15. See Chapter I, Section C.2(b). back to text

16. New Drugs and Indications in 2011. France is Better Focused on Patients’ Interests after the Mediator° Scandal, But Stagnation Elsewhere”, translated from Rev Prescrire, 2012, 32(340): 134-40. back to text

17. See www.who.int/medicines/areas/policy/access_noncommunicable/NCDbriefingdocument.pdf. back to text

18. UN document A/RES/66/2. back to text

19. See http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2007/a95078_eng.pdf. back to text

20. See http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/ WHO_EDM_PAR_2004.7.pdf. back to text

21. See www.who.int/childmedicines/prioritymedicines/en/ index.html. back to text

22. See Annex 5 in Forty-Sixth Report of the WHO Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations, available at www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/quality_assurance/expert_committee/TRS-970-pdf1.pdf. back to text

23. See www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2431-1074.pdf. back to text

24. Ibid. back to text

25. See www.gavialliance.org. back to text

26. See http://apps.who.int/gb/pip/pdf_files/OEWG3/A_PIP_ OEWG_3_2-en.pdf. back to text