D. Other trade-related determinants for improving access

Key points |

|

|

|

|

|

1. International trade and tariff data of health products

No country is entirely self-reliant for the products and equipment it needs for its public health systems – most rely heavily on imports. Trade statistics therefore provide valuable insights into the evolution of patterns on access to health-related products. The factors affecting imports influence availability as well as prices of health-related products and technologies, and thus have immediate consequences for access. Tariffs are one of the key factors influencing imports, but price and availability are also determined by non-tariff measures (e.g. licences, regulations and import formalities) and import-related costs, such as transportation. In addition, national distribution costs, such as wholesale and retail mark-ups and dispensing fees, may increase prices dramatically.

Analysing trade statistics and tariffs on health-related products is difficult in the absence of a well-defined classification of health products in WTO agreements and the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS) of tariff nomenclature (used to monitor international trade). Many products – such as chemical ingredients – have both medical and non-medical end uses. In the absence of a precise definition, this section reviews health-related products which are identified under 207 subheadings (334 tariff lines) of the HS for 139 countries. In all, this represents a total of 50,000 tariff lines for each of the years surveyed. The main categories are in HS29 (labelled as Organic Chemicals) and in HS30 (labelled as Pharmaceutical Products). One of the limitations of the data is that they do not reflect importation and immediate re-exportation. The products are clustered in six groups (see Table 4.2). While these categories are not exhaustive, they provide useful insight into trade in health-related products.

| Table 4.2. Public health-related products | ||||

| Group A | Pharmaceutical industry | A1 Formulations |

Nine tariff subheadings covering medicaments put up in measured doses and packaged for retail sale. |

Headings 3002 and 3004 of the HS nomenclature. |

| A2

Bulk medicines |

Six tariff subheadings covering medicaments not put up in measured doses for retail sale, i.e. sold in bulk. | Headings 3003 and 3006 of the HS nomenclature. | ||

A3 Inputs specific to the pharmaceutical industry |

57 tariff subheadings covering inputs specific to the pharmaceutical industry, e.g. antibiotics, hormones and vitamins. |

Headings 2936, 2937, 2939 and 2941 of the HS nomenclature. |

||

| Group B | Chemical inputs | B

Chemical inputs of general purpose |

73 tariff subheadings covering chemical inputs used by the pharmaceutical industry as well as other industries and which correspond to the WTO Pharmaceutical Tariff Elimination Agreement. | Several headings of Chapter 29 as well as headings 2842, 3203, 3204 the HS nomenclature. |

| Group C | Medical equipment, other inputs | C1 Hospital and laboratory inputs |

28 tariff subheadings covering bandages and syringes, gloves, laboratory glassware, diagnostic reagents, etc. |

Headings 3001, 3002, 3005, 3006, 3507, 3822, 4014, 4015, 7017, and 9018 of the HS nomenclature. |

| C2

Medical technology equipment |

33 tariff subheadings covering medical devices used in diagnosis or treatment covering furniture, X-rays, machinery, etc. | Headings 8419, 8713, 9006, 9018, 9019, 9021, 9022 and 9402of the HS nomenclature. |

Source: WTO Secretariat.

(a) International trade in health-related products

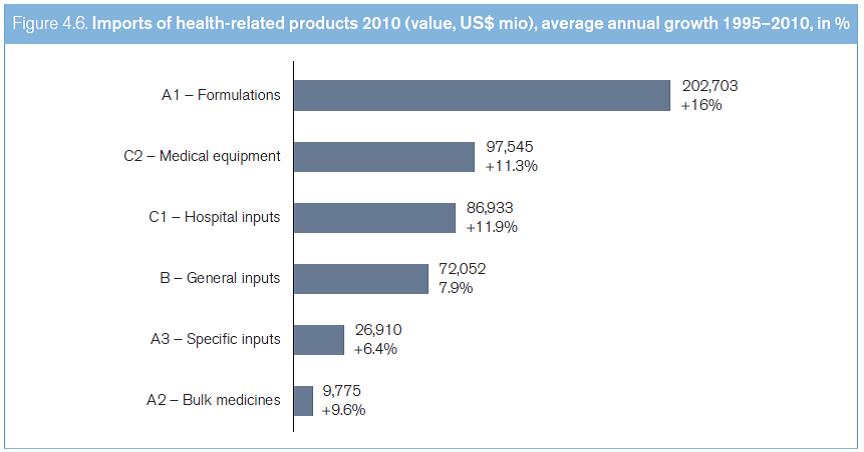

International trade in the six groups of health-related products experienced very dynamic growth from 1995 to 2010, rising from US$ 92 billion to about US$ 500 billion. This represents an average annual rate of growth of almost 12 per cent – almost double the average growth rate of general merchandise trade.1 In 2010, trade in health-related products accounted for approximately 4.2 per cent of global merchandise trade. As can be seen in Figure 4.6, most of the trade in health-related products relates to formulations (Group A1), which is one of the fastest growing sectors of the health industry (average annual growth of 16 per cent since 1995), followed by trade in medical technology equipment (Group C2, average annual growth of 11.3 per cent since 1995). Medicines, in bulk and in formulations, accounted for over 60 per cent of all trade in health-related products in 2010. This trade is dominated by a small number of countries. The European Union and the United States together account for almost 50 per cent of all world imports. Overall, developed countries imported almost 70 per cent of traded health-related products (see Table 4.3). Developed countries' dominance of this trade has changed little over the past 15 years, possibly explained by these economies' relatively high share of private and public expenditures for health care, and their greater integration into vertical supply chains, thus boosting trade flows (see Box 4.20).

Source: COMTRADE, WTO Secretariat.

| Table 4.3. International trade in health-related products: share of main importers, 2010, in % | |||||||

|

TOTAL |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

B |

C1 |

C2 |

| European Union | 26.3 | 20.8 | 24.4 | 37.8 | 26.4 | 34.9 | 26.9 |

United States |

21.9 |

25.6 |

14.9 |

12.9 |

16.7 |

17.4 |

25.0 |

| Japan | 6.6 | 6.0 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 6.6 |

Switzerland |

5.5 |

6.2 |

2.4 |

6.0 |

6.4 |

5.9 |

3.0 |

| China | 3.8 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 5.9 | 3.1 | 5.3 |

Canada |

3.7 |

4.7 |

3.9 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

3.7 |

3.4 |

| Russian Federation | 3.1 | 4.6 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

Australia |

2.7 |

3.6 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

3.0 |

| Brazil | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 1.9 |

Mexico |

1.9 |

1.6 |

3.1 |

1.7 |

2.5 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

| Republic of Korea | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 1.9 |

Turkey |

1.5 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

| India | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

Source: COMTRADE, WTO Secretariat.

A small number of players also dominate export trade (see Table 4.4), with the United States and EU member states exporting approximately 60 per cent of traded health products, and developed countries accounting for almost 80 per cent of such products. Some variations are evident between categories. In comparison with individual EU member states, China, the fourth largest exporter of health-related products, leads world exports in subgroup A3 (pharmaceutical inputs) and group B (chemical inputs). Some other developing countries rank higher in some categories: for example, Israel and India are significant exporters of medicines in bulk; and Mexico and Singapore are major exporters of inputs for hospitals and laboratories.

Overall, international trade has assumed increasing importance in ensuring supplies of goods required for public health, such as medicines, medical devices and other technologies. Of the 139 countries surveyed, only 24 were net exporters of health-related products in 2010.

Box 4.20. WTO "Made in the World Initiative": towards a measure of trade in value-added |

The patterns of global production and trade have changed considerably, and are now based on globally integrated production chains. Manufactured products consumed all over the world are often produced within international supply chains where individual companies specialize in specific steps of the production process. Increasing numbers of products are composed of parts and components with various geographical origins, such products should be labelled "Made in the World" rather than "Made in any single country". |

The trade taking place between various stakeholders in supply chains reflects their specialization in particular activities, and can thus be referred to as "Trade in tasks". The rise in global production has involved profound changes in international trade, mainly characterized by the marked increase of world trade in intermediate goods, the expansion of processing trade among developing countries and the important growth of intra-firm transactions. |

Conventional trade statistics do not necessarily show the real picture of international trade in a globalized economy. For example, the "country of origin" recorded for imports of final goods is often the last country in the production chain, and this ignores the value of production from other contributors (origins). In order to provide innovative approaches to international trade statistics, the WTO launched its "Made in the World Initiative" (MIWI) in 2011. This initiative is aimed at fostering new methodologies to compile information on trade in value-added indicators. In January 2013, in the context of the MIWI, the WTO and the OECD unveiled the first set of data of trade in value-added. |

| Table 4.4. International trade in health-related products: share of main exporters, 2010, in % | |||||||

EXPORTS |

TOTAL |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

B |

C1 |

C 2 |

| EuropeanUnion | 38.2 | 20.5 | 43.8 | 24.5 | 25.9 | 30.2 | 31.9 |

United States |

20.5 |

14.0 |

16.7 |

15.6 |

16.4 |

28.0 |

31.4 |

| Switzerland | 13.9 | 14.8 | 2.9 | 19.9 | 8.3 | 21.1 | 8.8 |

China |

6.0 |

0.6 |

3.3 |

24.1 |

17.8 |

5.5 |

4.7 |

| Japan | 3.2 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 2.6 | 5.1 |

Singapore |

3.0 |

2.4 |

0.6 |

3.3 |

6.6 |

2.1 |

2.6 |

| India | 2.6 | 2.8 | 6.5 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

Israel |

1.8 |

2.9 |

9.7 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

1.3 |

| Mexico | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 |

Canada |

1.6 |

2.7 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

| Australia | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

Republicof Korea |

0.8 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

0.5 |

1.3 |

| HongKong,China | 0.8 | 0.5 | 6.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

Brazil |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

Source: COMTRADE, WTO Secretariat.

Note: Names of WTO members are those as used in the WTO.

Next to some EU member states2 and Switzerland, the net exporters of health-related products include China, India, Israel and Singapore. The vast majority of developing countries are net importers of pharmaceutical products (see Tables 4.5 and 4.6).

| Table 4.5. Net exporters of pharmaceutical products (A1, A2, A3), 2010, US$ mio

|

|

European Union |

50,272 |

| Switzerland | 18,355 |

Israel |

4,984 |

| India | 4,839 |

Singapore |

3,751 |

| China | 622 |

Jordan |

241 |

| Iceland | 11 |

Source: WTO Secretariat.

| Table 4.6. Net importers of pharmaceutical products (A1, A2, A3), 2010, in US$ mio | |

United States |

-25,208 |

| Japan | -9,961 |

Federation |

-9,486 |

| Canada | -5,302 |

Australia |

-4,407 |

| Brazil | -4,044 |

Turkey |

-3,445 |

| Saudi Arabia | -3,251 |

Mexico |

-2,639 |

| Venezuela, Bolivarian Rep. of | -2,256 |

Republic of Korea |

-2,254 |

| Ukraine | -2,088 |

Africa |

-1,812 |

| Panama | -1,572 |

Algeria |

-1,572 |

| Thailand | -1,293 |

Iran |

-1,279 |

| Egypt | -900 |

Norway |

-899 |

| Colombia | -836 |

Source: WTO Secretariat.

Structural shifts were evident in general trade in health products between 1995 and 2010. Many countries moved to a trade surplus, indicating growth and diversity in production capacity, with surpluses aimed at export markets. A number of countries (e.g. Costa Rica, Ireland and Singapore) prioritized the pharmaceutical and medical sector in national development strategies. Vigorous growth in health-related products and strong global demand mean that development strategies targeting the production and trade of health-related products offer developing countries promising avenues for economic growth and diversification. China became a major exporter, exporting US$ 27.8 billion of health-related products in 2010, ten times its 1995 exports. From being a net exporter of health products (in all six categories), the United States became a very large net importer (only the Russian Federation and Japan import more). By contrast, the EU-27 (the 27 EU member states),3 which were net importers in 1995, exported more than they imported in 2010. For some countries, imports are highly significant domestically, even if they comprise a small share of global trade. Imports of health-related products represent 5 per cent or more of all imports for 40 countries in the world, with this share rising to 17 per cent in Panama, 14 per cent in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and 12 per cent in Burundi (see Table 4.7).

| Table 4.7. Share of health product imports in total national imports, in %

|

|

Panama |

17 |

| Switzerland | 15 |

Venezuela, Bolivarian Rep. of |

14 |

| Burundi | 12 |

Togo |

11 |

| Nicaragua | 9 |

Mali |

8 |

| Barbados | 8 |

Malawi |

7 |

| Australia | 7 |

EU-27 |

7 |

| Brazil | 7 |

Colombia |

6 |

| Polynesia | 6 |

Russian Federation |

6 |

Source: WTO Secretariat.

Source: Helble (2012).

Substantial, and widening, variations in per capita imports of health-related products were evident over the past 15 years between countries at different levels of development (see Figure 4.7), thus highlighting stark differences in access to medicines. Developed countries' per capita imports grew eightfold, from US$ 16.02 to US$ 127.42. Transition economies showed the strongest relative growth, rising from the lowest level of US$ 0.20 to US$ 48.21 in 2009. The rate for developing countries grew sixfold from US$ 1.63 to US$ 9.64. The per capita increase for LDCs was lowest and grew less, from US$ 0.65 to US$ 1.97. LDCs produce few medicines and rely very heavily on imports, and, consequently, these import statistics are reasonable indicators of overall consumption of medicines: therefore, despite a modest improvement, the relative level remains very low, particularly given the high disease burden in LDCs. Overall, developing countries, LDCs and transition economies, comprising 85 per cent of the world's population, account only for 30 per cent of imports and 20 per cent of exports of internationally traded health-related products.

(b) Tariff policy for health-related products

Tariffs or import duties on pharmaceuticals affect prices, protection for local production capacity and generation of revenue (Olcay and Laing, 2005). The WHO has recommended that countries "reduce or abolish any import duties on essential drugs" (WHO, 2001d). Initiatives such as the Malaria Taxes and Tariffs Advocacy Project call for reductions of tariffs on products including treated mosquito nets, artemisinin-based combination therapies, diagnostic tests, insecticides and related equipment. Patterns of tariffs applied to the six health-related product groups therefore have a direct bearing on access.

Tariffs on all groups of health-related products have been reduced since 1996 (Figure 4.8). Tariffs on pharmaceutical products (Groups A1 and A2) have been markedly reduced in developing countries and LDCs, and remained close to zero in developed countries. Tariffs on general purpose chemical inputs remained the most protected product category in all three country groups. Economies in transition displayed contrasting patterns: formulations (A1) were, and remain, the most protected group of products, while tariffs on specific inputs (A3) and on inputs of general purpose (B) were lowest. Economies in transition reduced tariffs less than the other three country groups. Developing countries seem to have structured tariffs on formulations (A1), bulk medicines (A2) and pharmaceutical inputs (A3), with a view to promoting the local production of medicines through tariff protection (Levison and Laing, 2003), especially for generic products, but commentators have questioned the consistency of such policies (Olcay and Laing, 2005). By contrast, LDCs apply lower tariffs on formulations (A1) than on bulk medicines (A2) and specific inputs into the pharmaceutical industry (A3). Economies in transition apply lower tariffs to bulk medicines, pharmaceutical inputs and chemical inputs, thus suggesting the intent to provide cheap inputs for domestically manufactured medicines.

Governments can increase tariffs applied to health-related products at any time, as long as such increases are within the limits of tariff ceilings that WTO members prescribe for themselves (called bound duty rates or "tariff bindings"). Sometimes, the gap between actually applied tariffs and the maximum WTO legal ceiling is very substantial (see Figure 4.9), creating doubts among traders about whether the effectively applied tariff rates might be increased again. Substantial cuts in bound rates to align them with actual rates, promote stability and predictability in tariff rates, and could promote trade in health products.

Source: COMTRADE, WTO Secretariat.

Governments sometimes apply special concessionary tariff regimes for certain strategic products, for example, waiving import duties on pharmaceuticals or health-related products so as to improve access. Several countries are reported (Krasovec and Connor, 1998) to apply such tariff exemptions for public health commodities, especially for not-for-profit purchasers.

FTAs frequently include provisions for preferential treatment between the agreement signatories. This may include reducing or removing import tariffs, which, in turn, results in more favourable market access than that afforded by multilateral (WTO) commitments. This section of the study only considers tariffs applied in the absence of such preferential deals, i.e. on a most-favoured-nation (MFN) basis. The difference can be very significant for LDCs and developing countries: for example, syringes may be imported free of tariffs from a country with preferential market access, but they may be subject to a 16-per-cent tariff when imported from other WTO members. As a result, procurement of health-related products is skewed towards partners in FTAs. A comparison of preferential tariff rates with those applied in the absence of preferences reveals that, for Brazil, China, Mexico, India, South Africa and Turkey preferential tariffs for all three product groups (A, B and C) fell between 2005 and 2009 and were lower than the WTO MFN rate (by at least 0.4 per cent). The gap between preferential treatment and MFN treatment has thus widened, with the lowest tariffs applying to medicines (A) and the highest tariffs applying to medical devices (C).

Overall, but with significant exceptions, tariffs on health-related products have reduced substantially during recent years, and only represent one of the cost factors in the complex equation that determines access and affordability.

Source: COMTRADE, WTO Secretariat.

However, tariffs often represent a cost increase at the beginning of a value chain (excise taxes, distribution services, mark-ups and retail services), so their impact on final prices may be considerably magnified by add-ons applied in the national distribution chain based on that higher import cost.

Apart from their impact on prices, tariffs also affect the conditions for local production initiatives – in terms of the cost of inputs such as chemical ingredients, the competitiveness and export focus of local producers, and the protection afforded by tariffs on imported products. The trend towards lower tariffs for specific and general chemical inputs into the pharmaceutical industry (groupings A3 and B1) may help boost competitiveness of the local pharmaceutical industry. The tariff data above do not provide conclusive insights into the effectiveness of efforts to build up local production capacities, but it is clear that tariffs are losing overall significance in these policy efforts. Box 4.21 briefly describes sectoral tariff negotiations related to public health in the GATT and the WTO.

Box 4.21. Sectoral tariff negotiations in the GATT and WTO |

During the Uruguay Round trade negotiations, some countries agreed to negotiate tariff reductions in specific economic sectors.4 |

In 1994, Canada, the European Communities,5 Japan, Norway, Switzerland and the United States concluded the WTO Pharmaceutical Agreement. These countries cut tariffs on pharmaceutical products and chemical intermediates used for their production (the "zero-for-zero initiative"), including all active ingredients with a WHO International Nonproprietary Name (INN). They agreed to periodically review and expand the list of items covered. The last such expansion took place in 2010. |

Also during the Uruguay Round, some WTO members agreed to harmonize tariffs on chemical products, bringing them to zero, 5.5 per cent and 6.5 per cent, in what is referred to as the "Chemical Harmonization" initiative. |

In 2006, in the context of the Doha Round negotiations on Non-Agricultural Market Access, some WTO members have put forward a proposal on "Open access to enhanced healthcare". It aims to reduce or eliminate tariffs and non-tariff barriers on a wide range of health-related products. The list of products to be covered includes chemical and pharmaceutical products, and a range of other items such as surgical gloves, bednets, sterilizers, wheelchairs, surgical instruments, orthopaedic appliances, as well as medical, surgical, dental and veterinary furniture. The proposal is still under consideration by WTO members. |

2. Competition policy issues

The importance of competition (antitrust) policy in promoting innovation and ensuring access to medical technology derives from its cross-cutting relevance to all stages and elements involved in the process of supplying medical technology to the patient – from the development and manufacture of such technology to its eventual sale and delivery (see Chapter II, Section B.2). While a full analysis of all competition policy issues involved in that process is beyond the scope of this study, this section outlines a number of areas where competition policy has direct relevance.6 The main focus in this section is on the link with the access dimension.

(a) Competition in the pharmaceutical sector

Once a pharmaceutical has been developed, one of the main determinants of access is affordability, for instance, the end-price paid by the consumer. The prices charged by manufacturers are an important factor in determining this end-price, and competition between different manufacturers has been found to have a beneficial effect on the affordability of and access to pharmaceuticals.

In that context, two forms of competition take place. The first form is between-patented-product competition, which is competition between manufacturers of different originator medicines within a given therapeutic class. The second form is competition between the originator companies and producers of generic products (as well as among the generic companies themselves), usually after expiry of the patent. The following sections discuss particular issues relating to competition law and policy.

(b) Application of competition law to manufacturers of originator products

Depending on the availability of alternative products, IPRs can influence the degree of competition in the pharmaceutical sector. The question of how competition law is applied to IP right holders has therefore plays an important role in the discussion on access to medicines.

In some countries, competition authorities have implemented a twofold strategy. On the one hand, they have conducted sector inquiries and have published reports, for example on the interrelationship between patents and competition, so as to gain a better understanding of competition concerns in the pharmaceutical sector and to identify relevant market structures. On the other hand, they have then used the knowledge gained to provide policy guidance and enforce competition law more effectively.

Several potentially anti-competitive strategies in relation to IPRs involving medical technology have been observed and documented. These strategies mostly are designed to extend patent protection for originator drugs and to prevent market entry by generic competitors after patent expiry (see Box 4.22). The following examples describe some anti-competitive practices that may be considered detrimental for access to medical technology.

(i) Strategic patenting

The European Commission Pharmaceutical Sector Inquiry Final Report (see Box 4.23) found that originator companies file for numerous patent applications (on process, reformulation, etc.) in addition to the base patent, with the aim of creating several layers of defence against generic competition. It showed that individual blockbuster medicines were protected by almost 100 INN-specific EPO patent families, which in one case led to up to 1,300 patents and/or pending patent applications across the EU member states. The report referred to such a multitude of patents as a "patent cluster". It described the effect of this strategy: that generic companies, even if they manage to invalidate the base patent before its regular expiry, still cannot enter the market.

Box 4.22. US federal Trade commission reports on patents and related enforcement actions |

In 2003, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC), an independent agency of the US government, published a report on the effects of patents on competition.7 The report proposed a number of recommendations designed to ensure that patents, while continuing to provide appropriate incentives for innovative activity, do not unnecessarily impede competition. A 2007 joint report by the FTC and the US Department of Justice highlighted the need to balance efficiencies with competitive concerns, in particular with regard to certain licensing practices.8 In 2011, the FTC published a report which focused on patent notices and remedies and their effects on competition.9 |

The FTC has also pursued numerous antitrust enforcement actions against both originator and generic medicines manufacturers at times when the agency had reason to believe that such companies had abused patent rights in violation of the antitrust laws. These actions have included cases of patent settlement agreements between originator companies and generic applicants, sham litigations, and agreements between generic drug manufacturers. The FTC has also addressed patent settlement agreements between originator companies and generic applicants in cases where the market entry of one or more generic applicants was delayed through manipulation of the 180-day exclusivity period provided by the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. |

The FTC has furthermore reviewed and, in many cases, blocked or placed appropriate conditions on mergers in health-related sectors that would have created anti-competitive effects. |

Box 4.23. European commission inquiry into the pharmaceutical sector and related enforcement action |

In 2008, the European Commission began an inquiry into the pharmaceutical sector to examine the reasons why fewer new medical technologies were being brought to market and why market entry of generic medicines seemed to be delayed in some cases. |

Based on an in-depth investigation of a sample of 219 medical pharmaceutical substances in the period between 2000 to 2007 in 17 EU member states, the final report found that the first generic version of medicines developed during this period had entered the market on average more than seven months after the originator medicines had lost exclusivity. |

The inquiry revealed that originator companies use a variety of instruments to delay the market entry of generics for as long as possible. Such instruments include: |

|

|

|

|

|

The report describes the filing of divisional patent applications as another strategy used by originator companies. This strategy involves keeping subject matter that is contained in a parent application pending even if the parent application as such is withdrawn or revoked. Divisional patent applications allow the applicant to divide out from a patent application (parent application) one or several patent applications (divisional application). Divisional applications must not go beyond the scope of the parent application. The division must be made while the parent application is still pending, leading to separate applications, each with a life of its own. These applications have the same priority and application date as the parent application, and, if granted, have the same duration as the parent application. In cases where the parent application is refused or withdrawn, the divisional application remains pending.

The European Commission stated that both practices are aimed at strategically delaying or blocking the market entry of generic medicines by creating legal uncertainty for generic competitors. However, the findings by the European Commission have not resulted in competition law cases related to the creation of "patent clusters" or the use of divisional patent applications.

(ii) Patent litigation and patent settlements

Litigation proceedings initiated by manufacturers of originator medical technology in multiple jurisdictions can constitute a deterrent to market entry of generics irrespective of the final outcome. Furthermore, in some cases, courts may grant preliminary injunctions in favour of patent holders while litigation is pending and before the ultimate determination of the validity of patents is made.

Similarly, settlement agreements that are reached during opposition proceedings or patent litigation between generic manufacturers and originator companies sometimes include negotiated restrictions on the generic companies' ability to enter the market, sometimes in return for a cash payment made by the originator company to the generic company (for the EU experience, see Box 4.24).

(iii) Refusal to deal and restrictive licensing practices

In some jurisdictions, and in particular circumstances, the refusal of an IP right holder to license the protected technology may be considered an anti-competitive abuse of dominance (see Box 4.25). Compulsory licensing can arguably provide an effective remedy in circumstances where a refusal to license may be abusive in character. It is important, however, to note that refusals to license per se are not necessarily actionable abuses. On the contrary, the right of such refusal may be viewed as implicit in the grant of the IP rights.

| Box 4.24. competition issues arising from patent settlements: the EU experience |

| Patent settlements are commercial agreements between private-sector companies to settle actual or potential patent-related disputes, for example, questions of patent infringement or validity in the context of opposition procedures or litigation. While patent disputes, like any other types of law suits between private entities, may legitimately be settled in order to avoid costly litigation, such settlements can have effects that restrict competition and can therefore be undesirable from the standpoint of competition policy. |

Follow-up studies after the European Commission Pharmaceutical Sector Inquiry report (see Box 4.23) have found that the number of patent settlements that are problematic under EU antitrust rules fell significantly in the years following the publication of the report. The European Commission's third report on its monitoring of patent settlements in the pharmaceutical sector, which was published in July 2012, confirmed that while the overall number of concluded settlements has significantly increased, the proportion of settlements that may be problematic for competition has stabilised at a low level of 11 per cent vis-à-vis 21 per cent in the findings of the sector inquiry. This shows that the Commission's action has not hindered companies from concluding settlements, contrary to fears expressed by certain stakeholders in that respect. At the same time, the monitoring exercises may have generally increased stakeholders' awareness of competition law issues, given the lower number of problematic settlements.11 |

Box 4.25. Abuse of dominance on antiretroviral markets in South Africa |

In 2003, the Competition Commission of South Africa concluded settlements with two major pharmaceutical companies relating to allegations that the two companies had abused their dominant position in their respective antiretroviral (ARV) markets by charging excessively high prices and by refusing to issue licences to generic manufacturers. |

The Commission agreed not to ask for the imposition of a fine and, in return, the companies undertook to: |

|

|

In 2007, a third major pharmaceutical company agreed to grant licences to produce and sell ARVs following a complaint about a refusal to license, which was brought before the South African Competition Commission. |

These cases concern settlements rather than fully litigated competition law decisions. Nevertheless, the settlements reached are understood to have contributed to the substantial reduction in prices of ARVs in South Africa.12 |

In many jurisdictions, other licensing practices, whose effects on competition are normally evaluated on a case-by-case basis, are regulated by competition law. Such practices may include:

- "Grant-backs" that legally grant back to the holder of a particular patent the right to use improvements made by a licensee to the licensed technology. Where such licences are exclusive, they are likely to reduce the licensee's incentive to innovate since it hinders the exploitation of his/her improvements, including by way of licensing any such improvements to third parties.

- "Exclusive dealing requirements" requiring a licensee to use or deal only in products or technologies owned by a particular right holder.

- "Tie-ins" or "tying arrangements" requiring that a given product or technology (the "tied product") be purchased or used whenever another product or technology (the "tying product") is purchased or used.

- "Territorial market limitations" limiting the territories within which products manufactured under licence may be marketed.

- "Field-of-use" restrictions limiting the specific uses to which patented or other protected technologies may be put by a licensee.

- "Price maintenance clauses" stipulating the price at which products manufactured under licence may be sold. Relevant clauses in licensing contracts can either be declared invalid in patent laws or other IP laws, or invalidated as violations of (general) competition law.

(c) Competition law and policy in relation to the generic sector

The effect of generic competition, including between generic manufacturers, on medicine prices after patent expiry has been highlighted in various studies carried out by the OECD and also carried out in developed countries, including Canada, EU member states and the United States. In general, these studies have found that savings from generic competition can be substantial. For example, a Prepared Statement by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) before a US Congressional Committee refers to possible savings in the range of 20 per cent to 80 per cent, depending on the number of generic market entrants.13 The European Commission found that in rare cases, for some medicines in some member states, the decrease in the average price index was as high as 80 per cent to 90 per cent.14 Other studies exploring these issues have been conducted by the Canadian Competition Bureau and the OECD.15

Where market entry of generics has occurred, the application of competition law to generic manufacturers is necessary in order to prevent anti-competitive practices by such companies and also oversee mergers that may restrict competition (see also Box 4.26 on applying competition law to generic manufacturers).

Aside from the enforcement of competition law, it is also important to ensure that competitive market structures are supported through regulation. Once patents on medical technology have expired, competition is best achieved by regulatory regimes that allow market entry of generics by removing unnecessary legal and administrative barriers while maintaining the required quality, safety and efficacy standards.

(d) Application of competition policy to the health care and retail sectors

Competition needs to be ensured not only with regard to manufacturers, but also with regard to the health care and retail sectors. Both restrictions of competition along the value chain (vertical restriction) and market restraints in the health care or retail sectors (horizontal restrictions) can have highly detrimental effects on access to medical technology. First, vertical mergers between different companies that operate along the value chain can pose a threat to competition. For example, the FTC has reviewed the acquisition by a research-based pharmaceutical company of pharmacy benefit management (PBM) companies. As well as carrying out a range of other activities, PBMs help to determine which prescription drug claims to reimburse. The acquisition may have resulted in the PBMs unfairly favouring the products of this pharmaceutical company, and thus the FTC required the PBMs to implement measures to remain neutral in the process that leads to decisions on which medicines are reimbursed.

Second, cartelization can restrict competition horizontally. Associations of pharmacies or pharmacists have been found in several OECD countries to have coordinated prices or restrict entry to the profession. In some cases, the associations restricted the ability of individual pharmacists to deal with third-party payers individually, thus establishing control over possible defectors and stabilizing cartel agreements.

At the same time, both public-sector initiatives and contracted or franchised NGO participation in retail have been found to increase competition and improve access to low-priced medical technology. For example, Uganda has contracted non-profit organizations to provide health services, and has allowed them to establish retail pharmacy outlets selling medical technology at affordable prices.

(e) The role of competition policy with regard to public procurement markets

The role of public-sector procurement and distribution is not to be underestimated. Competition policy is relevant in two key respects.

First, good procurement policies can maximise competition in the procurement process. Moreover, it can be cost-effective to procure bulk quantities of medicines.16 However, this may mean that a balance needs to be struck between achieving the lowest price in a given tender (through bulk purchases) and maintaining a competitive market structure over the medium to longer term.

Second, competition policy has an important role to play in preventing collusion among suppliers of medical technology. Although transparency is generally considered conducive to integrity in the procurement process, it can also facilitate anti-competitive behaviour by, for example, facilitating the ability of competitors to match each other's prices. Competition policy and law therefore need to complement general procurement regulations and practices in order to guard against such behaviour, and competition authorities should be encouraged to monitor anti-competitive behaviour not only with regard to competition in private markets but, equally, with regard to competition in public markets for medical technology (Anderson et al., 2011).

Box 4.26 Applying competition law to generic manufacturers |

The FTC has found cases where generic companies have entered into anti-competitive agreements so as to control markets for generic medical technology and ancillary markets. For example, in 2000, the FTC found that four companies had concluded exclusive licensing agreements for the supply of raw materials for producing lorazepam and clorazepate, which resulted in a dramatic increase in the price of these products. In a move designed to not only deter such behaviour, but also to compensate the public for the welfare losses incurred, the FTC ordered one company to pay US$ 100 million to consumers and state agencies who had suffered losses as a result of excessive prices. |

The FTC has also reviewed takeovers of one generic manufacturer by another to assess whether the merged company would reduce competition in medical technology markets. For example, in the case of a merger of two generic companies in 2006, the FTC required the companies to divest certain assets needed to manufacture and/ or market 15 generic products.17 |

1. The annual growth rate of world merchandise trade in value terms was about 6.1 per cent according to the WTO Statistics Database. back to text

2. Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom. back to text

3. Intra-trade of today’s 27 EU member states has been consolidated into EU-27 group since 1995, in order to work over a stable group over the period analysed. back to text

4. See WTO document TN/MA/S/13 for further information regarding sector-specific negotiations in goods in the GATT and WTO. back to text

5. Refers to the European Communities and its 12 member states in 1994. Since then, the European Communities has evolved into the European Union and its 27 member states. All countries which adhered to the European Union since 1994 have subscribed to the same tariff commitments of the previous European Communities with respect to the elimination and harmonization of tariffs in health-related products. back to text

6. For additional details, see Müller and Pelletier (forthcoming). back to text

7. See www.ftc.gov/os/2003/10/innovationrpt.pdf. back to text

8. See www.ftc.gov/reports/innovation/ P040101PromotingInnovationandCompetitionrpt0704.pdf. back to text

9. See www.ftc.gov/os/2011/03/110307patentreport.pdf. back to text

10. Sources: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/ pharmaceuticals/inquiry/; http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=MEMO/12/593&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en. back to text

11. Source: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/ pharmaceuticals/inquiry/. back to text

12. Sources: http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/people/tfisher/ South%20Africa.pdf; www.wcl.american.edu/pijip_static/ competitionpolicyproject.cfm. back to text

13. See www.ftc.gov/os/testimony/P859910%20 Protecting_Consume_%20Access_testimony.pdf. See also www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/ OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ucm129385.htm. back to text

14. See http://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/ pharmaceuticals/inquiry/preliminary_report.pdf. back to text

15. See: www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/vwapj/GenDrugStudy-Report-081125-fin-e.pdf/$FILE/ GenDrugStudy-Report-081125-fin-e.pdf; and www.oecd.org/regreform/liberalisationandcompetition interventioninregulatedsectors/46138891.pdf. back to text

16. For further background information, see www.oecd.org/document/25/0,3746,en_2649_37463_48311769_1_1_1_37463,00.html. back to text

17. Source: www.haiweb.org/medicineprices/05062011/ Competition percent20final percent20Maypercent202011.pdf. back to text