AGRICULTURE NEGOTIATIONS: FACT SHEET

The Bali decision on stockholding for food security in developing countries

UDPATED 27 NOVEMBER 2014

At the 2013 Bali Ministerial Conference, much of the focus was on a proposal to shield public stockholding programmes for food security in developing countries, so that they would not be challenged legally even if a country’s agreed limits for trade-distorting domestic support were breached. Ministers agreed that their solution would be interim, until a permanent solution was found. But by the end of July 2014, members were deadlocked again, until a breakthrough was agreed in November.

NOTE: THIS UNOFFICIAL EXPLANATION HAS BEEN PREPARED BY THE INFORMATION AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS DIVISION OF THE WTO SECRETARIAT TO HELP THE PUBLIC UNDERSTAND THE AGRICULTURE NEGOTIATIONS. IT IS NOT AN OFFICIAL SUMMARY OF ANY TEXT.

MORE FACTSHEETS (AGRICULTURE):

> “The boxes” in domestic support

> Tariff reduction methods

> Unofficial guide to agricultural safeguards

> Up-to-date factsheet list

SEE ALSO:

> Agriculture negotiations

> 2004 agreed framework

> 2005 Hong Kong Ministerial Declaration

> 2013 Bali Ministerial Conference

> The Bali Package

Need help on downloading?

> Find help here

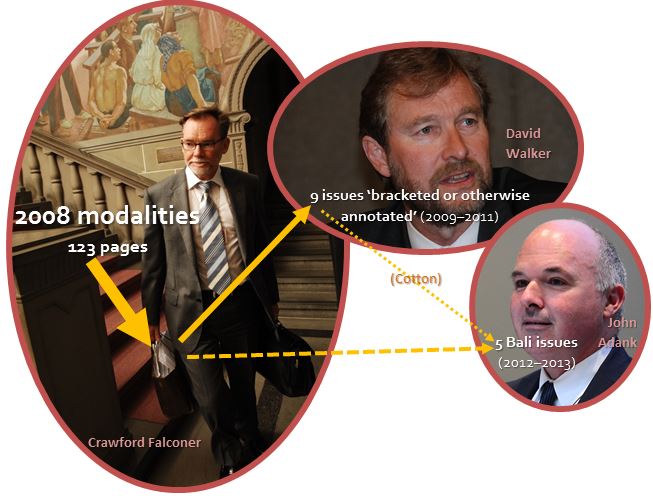

The stockholding proposal was one of four agriculture issues (plus cotton) selected out of a considerably broader agenda in the stalled Doha Round negotiations. Members picked these issues for Bali following a 2011 decision to change the approach in an attempt to get the talks moving again.

The relationship between the Bali issues and the broader Doha Round is explained here (click the image to follow the link):

On this page

- What’s the problem?

- Technical note

- What’s been proposed — and when?

- What was agreed in Bali?

- And after Bali?

- Timeline: evolution of the ‘public stockholding’ proposal

Trade-distorting domestic support (the “aggregate measurement of support“ or AMS, sometimes called “Amber Box” support) is calculated as the difference between the present support price and the 1986–88 reference price multiplied by production that is eligible for the support.

For most developing countries, the resulting amount has to be within 10% of the value of production (the “de minimis“ level). The few that started off with higher support levels ended up with agreed AMS limits that are above the 10%, provided they reduced their support:

(Support price — reference price) x (eligible production) ≤ 10% of the value of production (or other agreed limit)

Some members see the fixed reference prices as a way to prevent countries — particularly major players in agricultural trade — from using inflation to increase the support they are allowed. The reference period was 1986–88, the first three years of the Uruguay Round negotiations which produced the present Agriculture Agreement and members’ commitments.

What’s the problem?

The Bali decision on stockholding arises because some developing countries fear they could breach the limits they have agreed on trade-distorting domestic support — ie, support that influences prices and quantities. The stockholding programmes are considered to distort trade when they involve purchases from farmers at prices fixed by the governments, known as “supported” or “administered” prices. Normally the support is within the agreed limits (see technical note) but some countries fear this might not always be the case. (Purchases at market prices are not counted as supported.)

The concern is only on the purchasing side because there are no limits on supplying cheap or free food specifically to the poor or malnourished.

back to top

What’s been proposed — and when?

The “public stockholding” proposal dates back to the early years of the agriculture negotiations and was first included explicitly in an African Group proposal in 2002 (see “evolution” below). For over a decade, various versions of the proposal sought effectively to include this among “Green Box” supports, which are allowed without any limit because they do not distort trade or do so minimally (see Annex 2 of the Agriculture Agreement).

However, the Green Box explicitly excludes price support. A number of countries were concerned that stockholding proposals involving support prices would alter the Green Box’s definition (and therefore the whole “architecture” of the Agriculture Agreement itself). As a result, some of the suggested compromises included changing the agreed limit without putting these purchases in the Green Box. There was no consensus on any of these ideas.

It wasn’t until 2013 — a few months before the Bali Ministerial Conference — that alternative ideas surfaced in the talks (see the chairperson’s 23 May 2013 report to members and “evolution” below). They included altering the way trade-distorting support is calculated by recalibrating the external reference price instead of fixing it in 1986–88, using a different method of taking inflation into account, or a “peace clause” shielding any breaches of the agreed limits from legal challenge. Also discussed was redefining “eligible production” — which is one part of the calculation of trade-distorting support (see technical note) — to mean the amount actually bought instead of all the produce that could have been sold to the government.

back to top

What was agreed in Bali?

The “peace clause” was the approach adopted in Bali, but with conditions added to deal with fears that stockholding programmes involving purchases at supported prices could affect other countries. Governments seeking the shelter of the peace clause have to avoid distorting trade (ie, affecting prices and volumes on world markets) or impacting other countries’ food security, and to provide information to show they are meeting those conditions.

There was no consensus on other proposals because a number of members — developing and developed — had concerns about changing the disciplines on domestic support, particularly the nature of the Green Box.

The “peace clause” is an interim solution. Members agreed in Bali to find a permanent solution by 2017 (the 11th Ministerial Conference) and that the interim solution would remain in force until then.

Back to top

And after Bali?

New difficulties emerged after Bali, which were not resolved until the General Council meeting of 27 November 2014, almost a year after the Ministerial Conference.

After Bali, the first proposal for a permanent solution came from the G–33 on 16 July 2014, which essentially repeated the group’s 2012 pre-Bali proposal to move these programmes into the Green Box. The proposal also called for a permanent solution by the 2017 deadline agreed in Bali.

In the General Council on 25 July 2014, India, a G–33 member, complained of slow progress on the permanent solution and called for a decision on this by the end of 2014. Because of the slow progress, India said, it could not proceed with adopting the legally polished trade facilitation text despite agreement in Bali to do so by 31 July. From then, members were deadlocked on how to proceed.

One question that arose was whether the interim “peace clause” would still apply if members failed to agree on a permanent solution by the 2017 deadline. Over the months, a number of members said they were prepared to clarify that it would continue to apply until a permanent solution is agreed, and eventually this was the basis for breaking the deadlock.

On 27 November, the General Council adopted decisions that would allow the trade facilitation text to go ahead, clarify the public stockholding proposal and allow work on it to continue and allow a programme for completing the Doha Round negotiations to proceed, almost six months later than originally envisaged.

On public stockholding, the “peace clause” was confirmed, but the way it was described was now firmer: members would “not” challenge these programmes legally under the Agriculture Agreement — the original decision said they would “refrain from” doing so. The conditions also remained unchanged: Governments seeking the shelter of the peace clause had to avoid distorting trade (ie, affecting prices and volumes on world markets) or impacting other countries’ food security, and to provide information to show they were meeting those conditions.

Members clarified that the “peace clause” would remain in force until a permanent solution was agreed, even if that meant going beyond the 2017 deadline. Although the reference to the 2017 Ministerial Conference remained, members also agreed to strive for a permanent solution by the end of 2015.

They spelt out that the permanent solution should be found through meetings of the agriculture negotiations, but in “dedicated sessions” that would be accelerated and separate from the rest of the Doha Round agriculture talks. And, they said, negotiations would also “continue to progress” on all three pillars of the agriculture negotiations as a whole — domestic support, export subsidies and related issues, and market access.

Back to top

Timeline: evolution of the ‘public stockholding’ proposal

ie, “public stockholding for food security in developing countries”, specifically, in the Agriculture Agreement: Annex 2’s paragraphs 3 and 4 and footnotes 5 and 6

Date(s) |

Proposal or document |

Main point(s) |

20 November 2002 |

African Group proposal JOB(02)/187 |

Removes reference to AMS (trade-distorting domestic support) calculations, effectively putting the programmes in the unlimited Green Box |

18 December 2002 |

Chaiperson’s overview TN/AG/6 |

Working hypothesis and variations range from keeping existing provisions to removing reference to AMS (effectively putting market price support in the Green Box) |

17 February 2003 |

First draft “modalities” TN/AG/W/1 and TN/AG/W/1/Rev.1 |

Exempts developing countries from the requirement that food security stockpiles have to correspond to “predetermined targets” |

6 April 2006 |

African Group TN/AG/GEN/15 |

Removes reference to AMS calculations, effectively putting market price support in the Green Box |

12 July 2006 |

Draft possible “modalities” TN/AG/W/3 |

Excluded from AMS calculations, effectively putting the programmes supporting low-income or resource-poor producers in the Green Box |

1 August 2007 |

Revised draft “modalities” TN/AG/W/4 |

AMS calculation covered by de minimis |

8 February 2008 |

Revised draft “modalities” TN/AG/W/4/Rev.1 |

AMS allowed up to de minimis of 15% (product specific) and 10% (overall) |

19 May 2008, |

Revised draft “modalities” TN/AG/W/4/Rev.2, TN/AG/W/4/Rev.3, TN/AG/W/4/Rev.4 |

Excluded from AMS calculations, effectively putting the programmes supporting low-income or resource-poor producers in the Green Box |

13 November 2012 |

G–33 proposal for Bali, JOB/AG/22 |

Excluded from AMS calculations, effectively putting the programmes supporting low-income or resource-poor producers in the Green Box |

3 October 2013 |

G–33 proposal for Bali, JOB/AG/25 |

For the “interregnum” until the Agriculture Agreement has been amended — three options: altering the AMS calculation by recalibrating the external reference price, alternative method taking inflation into account, or a “peace clause.” This is the first time that adjusting reference prices or a “peace clause” appears in a paper |

7 December 2013 |

Bali Ministerial Decision WT/MIN(13)/38 |

“Peace clause” shields existing programmes of developing countries against legal challenge if support leads them to exceed agreed limits |

17 July 2014 |

G–33 proposal for a permanent solution JOB/AG/27 |

(Repeats 2012 proposal) Excluded from AMS calculations, effectively putting the programmes supporting low-income or resource-poor producers in the Green Box. Calls for a permanent solution by 2017 (11th Ministerial Conference) |

27 November 2014 |

General Council decision WT/GC/W/688 |

Bali interim “Peace clause” confirmed; wording slightly tightened; members agree to strive for permanent solution by the end of 2015; they clarify that interim solution remains until permanent one agreed |

Note: some other proposals would also have implications for this issue without referring specifically to public stockholding. For example in 2001 India proposed (G/AG/NG/W/102) that all product specific support given to low income and resource poor farmers should be excluded from calculations of trade-distorting support (AMS).

Place the cursor over a term to see its definition:

About negotiating texts:

Issues:

• Blue box

• box

• special safeguard mechanism (SSM)

> More jargon: glossary

> More explanations